Under Cover: The Parallax View (1974)

June 17, 2021 By Go BackOf all the intimations of dark conspiracy that insinuated into Hollywood movies in the 1970s, none suggested the utter hopelessness of escape with quite the devastating power and totalizing dread of Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View (1974). Other movies might have depicted paranoia as a creeping social condition or let it slip into the fabric of the narrative. But The Parallax View stood alone in inducing its condition. It’s a movie made to make the fear of intangible forces as rational as the times seemed to call for. As Pakula reportedly clarified for his star Warren Beatty, “If the picture works, the audience will trust the person sitting next to them a little less at the end of the film.”

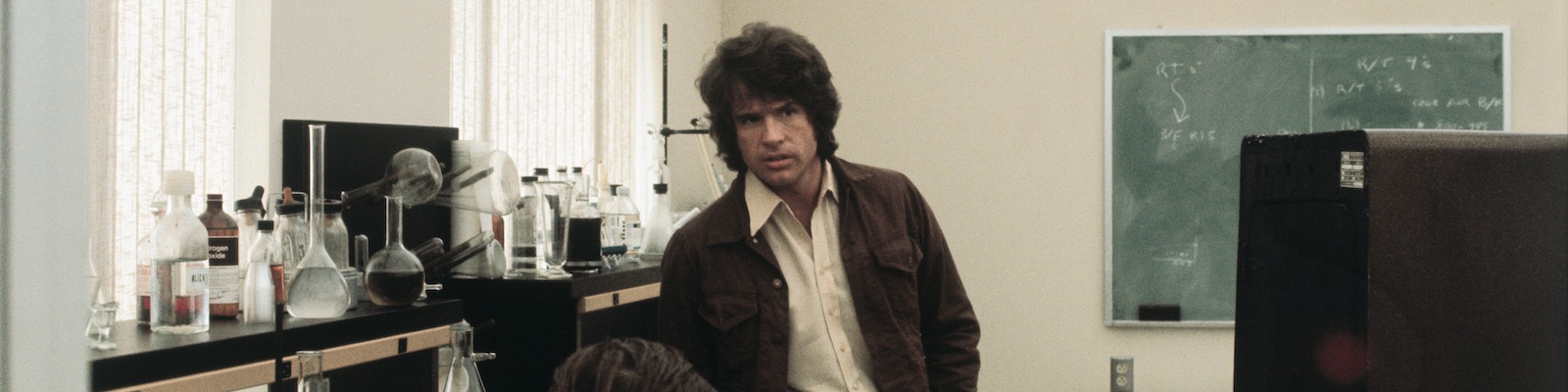

Based on a 1970 novel by Loren Singer, producer-turned-director Pakula’s fourth feature film imposed considerable alterations and shifts in emphasis on the original story, almost all of them seemingly in the service of generating a pervasive atmosphere of immersive anxiety. The journalist ‘hero’, played by Warren Beatty in the film, witnesses the assassination of a liberal presidential hopeful at a fund-raising rally, and subsequently embarks on his own undercover investigation when a number of witnesses to the event begin to expire prematurely and under dubious circumstances. His lone-wolf mission leads him to offer himself as a likely candidate for an assassin-recruiting organization called ‘The Parallax Corporation’, but his feigned credentials as a suggestible sociopath ultimately render him vulnerable to the fate named in the Dallas police station by Lee Harvey Oswald: he becomes a perfect patsy.

Departing from the book, Beatty’s Joe Frady does not witness the assassination – which is followed by a skirmish atop the Space Needle in Seattle that sees the prime suspect slipping to his death with only the sound of wind and flapping flags heard – and only becomes engaged by the rumours of conspiracy when a reporter who did see the killing, played by Paul Prentiss, winds up dead – an apparent suicide – after trying to convince Frady she thinks she may be next on the list of inconvenient witnesses.

Despite the reasonable doubts of his editor (Hume Cronyn), Frady plunges into the shadows behind the senator’s death until he is eventually consumed by them and disappears. Without, it bears noting, much of a sound made or witnesses to the departing. As much as anything this, along with top-of-his-game Gordon Willis’s space-and-shadow-prone cinematography and Michael Small’s sparsely martial score, is instrumental to the texture of all-consuming dread The Parallax View manifests to such unnerving effect: the silence that attends the murder and disappearance of people, augmented only by the distant sounds of America conducting itself as though all were business as usual. Which ultimately may be only too true, at least in this movie’s approximation of America a decade after Dallas: this sinister shit is business as usual.

Structurally as well as stylistically, the movie moves from the realm of first-person investigative thriller, wherein we follow Frady into the shadows and see only what he does, to something else entirely: a universe unhinged from cause-and-effect, clue-and-solution, mystery-and-resolution. Midway through the film, in a break in diegetic convention that’s as shattering and disorienting as the melting film frame in Persona or James Woods’ head-first plunge into the TV screen in Videodrome, Frady sits down – in the distance in a dark room – for a Parallax-produced orientation film. A four-minute exercise in Madison-Avenue-meets-Eisenstein-inspired dialectical montage designed to instil in the receptive viewer a sense of homicidal rage against those forces which are perverting American ideals, the training film is such a bravura exercise in self-contained persuasive semiotics it almost breaks the movie apart. Disengaging entirely from Frady’s point-of-view in favour of an unmediated presentation of the video directly to us, the movie compels you to emerge from the screening into the world it has evoked and summoned. In effect, from that point on, Frady not only loses agency both as an investigator and an individual, it’s entirely open to question – and remains that way – whether he was ever acting outside of a script entirely written just for him. This is the point where paranoia shifts from the subject of Pakula’s film to the condition it replicates.

One of the purest examples of the noir resurgence of the 70s, The Parallax View suggests the necessary classic-period conditions of terrifying isolation, fear and malevolent (but impersonal) external forces without any nods to borrowed convention or rear-view self-referentiality. Less homage than incarnation, it’s as organic an expression of its own period’s anxieties as postwar film noir was of its day. While it’s true the narrative circumstances – of a man trapped by fate – and the style – an enveloping world of shadows – are as elementary noir as it gets, the affiliation here is based in a shared conviction that the world turns according to plans and forces that can neither be stopped nor avoided. The open question at the end – surely one of the bleakest in a decade of bleak ends – is whether Frady ever really had any agency at all, or if everything was all part of the Parallax plan.

One of the most remarkable, not to mention currently unthinkable, indications of the movie’s hard-wiring to both its moment and its condition is the use of its star. While featuring one of the most marketable marquee names of its day, The Parallax View stresses Beatty’s ultimate dispensability from the moment he appears in the background of the crowd gathered at the Space Needle. Lacking the credentials to gain access to the event, Beatty’s Frady is subliminally positioned as a disenfranchised outsider from the outset. Apart from the anonymous woman spotted in his living room when Prentiss arrives to appeal for his help, Frady seems to have no personal affiliations with anyone except his editor, and it is part of the movie’s overall strategy of incremental disorientation to nudge the character constantly toward the edge and away from all connections to that business-as-usual America glimpsed and heard carrying on in the background. He seems almost always alone except when meeting with Cronyn or being vetted by the Parallax Corporation’s unnervingly calm field representative (Walter McGinn), and the tactical requirements of being an ‘undercover’ investigative journalist only ensure that he’s perilously adrift and ripe for plucking.

While Willis’s ravishing cinematography most strikingly emphasizes the emptiness of space and Frady’s marginality in it, the entire design of the movie is directed toward the gradual disappearance of its protagonist into the gathering dark. From the moment he sits in that distant chair to watch the assassin’s recruitment film, a vaguely recognizable blip in the centre of the screen, Frady is lost to us and himself. In the end that blackness closes in, sealed with an official stamp of Congressional insistence that what we’ve just witnessed didn’t really happen.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram