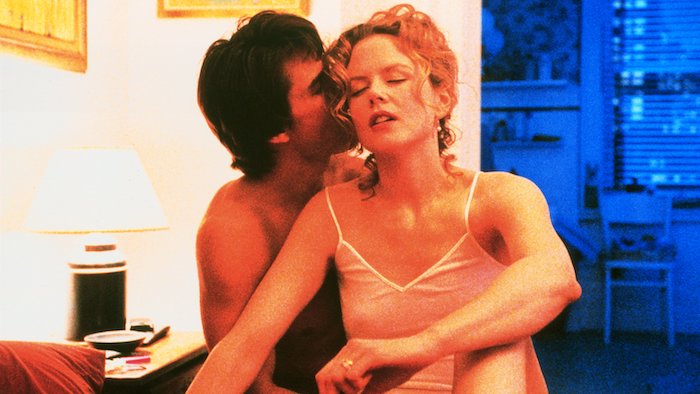

The Big Tease: Eyes Wide Shut

May 1, 2020 By Go BackThe most popular movie on the planet for two days in July, 1999, Stanley Kubrick’s posthumously released bad dream movie Eyes Wide Shut probably ranks as the worst first date movie ever. Considering how many people flocked to this hungrily-anticipated, secrecy-enshrouded exercise in frustrated desire, you’ve got to wonder how many of those first dates were lasts as well. Budding romance requires oxygen, and this movie left you gulping for it.

It was, of course, only to be expected that Eyes Wide Shut was that unexpected. Was no one paying attention? From the moment Stanley Kubrick, a self-taught Bronx-born photographic prodigy and aspiring filmmaker, was able to do precisely what he wanted, he was in the head-scratching business. From Lolita forward, Kubrick positioned himself as a commercially savvy maker of studio-backed art movies, and his example – at once inspirational and impossible – was nothing short of a rallying call to New Hollywood. No other single American filmmaker of his generation had quite the same grip on the system’s junk as Kubrick did, and he never stopped squeezing. Any wonder then that his final movie, which cast Tom Cruise as a kind of urban-yuppie Ulysses lost and adrift on a sea of temptation, should be about not getting laid. All whimper and no bang.

Nothing less than a master of controlled anticipation, Kubrick generated something of a frenzy out of the vacuum surrounding Eyes Wide Shut’s pre-production, production and release. Based on a largely forgotten novel of the Freudian jazz age, Kubrick’s first production since Full Metal Jacket (1986) – another grenade tossed into the vacuum of expectations – was cloaked in prurient possibility. Were Hollywood’s most closely watched couple – no slouches in the information management department themselves – actually going to be doing it in the name of, um, art? Was it true that Kubrick’s goal was exploit the public knowledge of the couple’s instability by casting them as the pre-millennial Liz and Dick? Was it true that the unprecedented four hundred day production schedule indicated a domestic power play in the production itself, and that the director’s notorious affinity for multiple takes, was a deliberate strategy to wear down any confusion about who would have the last word? Was death Stanley Kubrick’s final bird-flip to expectation?

Kubrick passed three months before the movie’s scheduled release – and mere days after he turned his cut into the studio – which did nothing to abate the tides of speculation. Had Kubrick really finished the film, considering his legendary capacity for final cut filibustering? Was the studio, and its besieged Scientologist superstar, at work re-editing and censoring all the naughty bits? Would Kubrick’s last word be heard? And what in God’s name would that be?

The movie itself ends with a humdinger: it’s the colloquial word for the act everybody was talking about but nobody was doing during the preceding two and three quarter hours. So, asks the repentant prodigal husband of his wife as their daughter cavorts in a Christmastime toy store, what do we do now?

“F—k,” she answers. “Directed by Stanley Kubrick,” says the screen. “Is that it?” say the rest of us.

Naturally, some among us believed that simply could not be it, and that nefarious forces must have tampered with the dead god’s vision. However independently they might have otherwise lived, Tom and Nicole presented a Bill and Hillary-esque wall of unity when it came to insisting the movie was wall-to-wall Kubrick, that not a frame had been altered or excised from director’s final cut, and basically that Eyes Wide Shut was exactly the movie the late Stanley Kubrick had chosen to bestow as his last from here to eternity.

F—k indeed. What were we expecting? In many ways, Eyes Wide Shut should have surprised no one. The story of a man cast adrift in his own delusions is boilerplate Kubrick. Cruise’s Dr. Bill Harford is a clueless pilgrim through existential chaos. A fellow traveller to Lolita’s Humbert Humbert, the astronauts in 2001, Barry Lyndon, The Shining’s Jack Torrance, Matthew Modine’s Pvt. Joker in Full Metal Jacket or even Alex in A Clockwork Orange – men so lost in their own heads the gap between projection and perception has completely merged. All movies require frontiers, and Kubrick’s has always been the terrain beyond sanity. Even his early rep-making films noir – Killer’s Kiss (1955), Fear and Desire (1953) and The Killing (1956) – which provided Kubrick with a generic template involving protagonists who stumble like refugees into the dark side, were accounts of what happens when one follows one’s worst and irresistible impulses.

With Eyes Wide Shut, Kubrick returned to those treacherous streets. An almost cardboard cutout of noir male desperation, Cruise finds himself drawn into the night, and down those studio-built Manhattan dead ends – in a New York as stylized, fake and alluring as any since Scorsese’s New York, New York (1977) – until he confronts the shattering reality of who he really is. People scoffed at Cruise’s unwavering cluelessness, deemed the movie’s orgiastic masked ball ridiculous and insisted all that sophomoric jazz with the masks was just embarrassing. But what open eyes could possibly fail to see Kubrick was just steering himself, and us, right back into home port? Could even the title have been a deliberate indication of how Stanley Kubrick knew we would react?

The better to maybe come back again. This time alone, and this time with eyes wide open.

Find the next playtimes for Eyes Wide Shut on Hollywood Suite

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram