Raising the Dead: The Power and Influence of George A. Romero’s Zombie Urtext

April 28, 2020 By Go BackWatching Night of the Living Dead fifty years after its original release is a remarkably fresh and lively experience. A rare occurrence in the horror genre where something that was terrifying in 1968, continues to issue forth spine tingles and substantial eeriness to viewers today. And while director George A. Romero could never have predicted the monumental impact he’d make on the film industry, it should come as no surprise that his singular vision for what would become known as the zombie film would captivate audiences and future filmmakers for decades to come. To this day, all zombie films, and indeed many non-zombie films owe Night of the Living Dead and Romero a debt of gratitude. The zombie genre has come a long way – and its zombies have ramped up their sprinting speeds re: 28 Days Later (2002), The Walking Dead (2010–), and World War Z (2013) – yet in every zombie-centric narrative, lies Night of the Living Dead‘s DNA. 50 years later we’re still watching it and as Hollywood Suite’s original doc Raising the Dead: Re-examining Night of the Living Dead makes clear, we’re still defining its historical impact and endlessly wondering how a low budget, independent B-film became one of the most iconic films of the twentieth century.

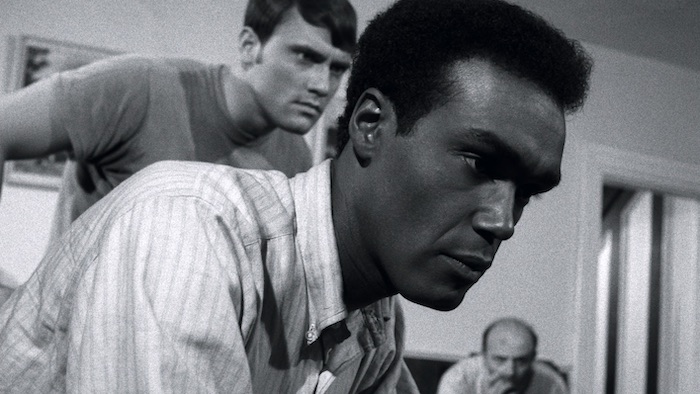

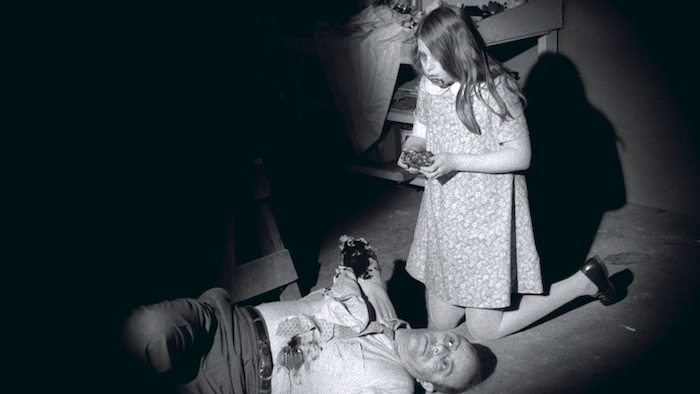

The Hollywood Suite original Raising the Dead offers a modern take on the Romero zombie phenomena. The documentary balances memories of the film’s production from those who were there – Kyra Schon, the actress who played the iconic child ghoul, as well as Russell Streiner who co-produced the film and portrayed Johnny – with modern assessments from historians and critics regarding the film’s importance to a variety of historical topics. Produced at the height of the civil rights movement – the same year that both Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. were assassinated – as well as in the midst of an “un-winnable” war in Vietnam, Night of the Living Dead reflects more of society’s fears than the average horror film. As such it operates as a time capsule of sorts, one where politics are veiled as threatening zombies, or as they are called in the film, ghouls (never is the term “zombie” mentioned).

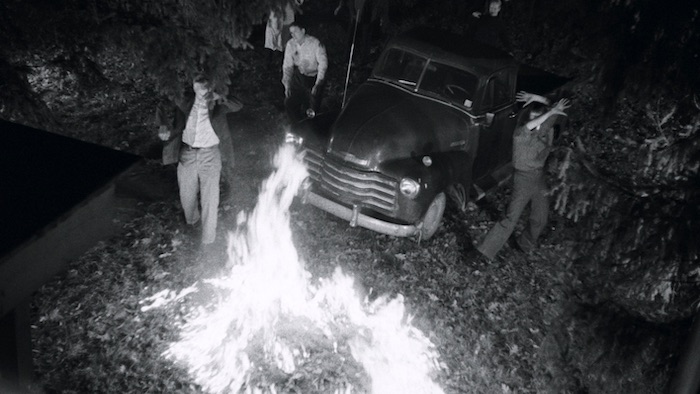

Filmed in black and white at a time when the industry standard and market demands dictated the more expensive colour stock, Night of the Living Dead’s monochrome style somehow adds more authenticity and doom to the film (check out Raising the Dead’s monochrome version On Demand to experience this effect for yourself). And while it may seem this was a budgetary choice on Romero’s part, it was intentional and metaphorical. Like a surveillance camera capturing the horrific developments of a society unravelling, stripping colour away somehow eliminates distraction. With Night of the Living Dead’s immediate popularity, a colourized version was released (primarily for television) in the 1980s – an effect of the film’s public domain status. Watching this “cheapened” version today in a manner that was in no way authorized by Romero, you appreciated the original’s black and white output for its slickness, and, somewhat surprising for a DIY horror film, its elegance.

Because of its failure to meet copyright rules in 1968 and falling into the public domain, pretty much anyone could exhibit, broadcast and even “re-interpret” Night of the Living Dead. But that isn’t to say that Romero didn’t permit, and at times oversee notable remakes and re-imaginings beyond his own sequels. For their 1990 remake of Night of the Living Dead, which featured an updated and adapted screenplay by Romero, the original’s producers Russell Streiner and John Russo turned to Romero alum Tom Savini – the special effect prosthetics master responsible for all Romero gore since Martin and Dawn of the Dead both released in 1978 (he also played the leader of the motorcycle gang in Dawn). Savini, known affectionately as “the King of splatter” wanted his version to be relatively light (for Savini, at least) on horrific gore. Wanting to honour Romero’s original, he sought realism and an arthouse feel, utilizing historic footage of concentration camp medical experiments and modern autopsies. Today, the remake is far more appreciated than it was upon its release. It was a film that struggled to find an audience and perhaps suffered from such a beloved and cherished forbearer – after all, how could it ever live up to Romero’s original?

Prior to Savini’s remake, Night of the Living Dead producers Streiner and Russo adapted the former’s follow-up book Return of the Living Dead in 1985. Released under the same title but without Romero’s participation (in their parting of ways after the original, Romero retained the rights to sequels but Russo retained the rights to any titles related to the “Living Dead” name), Return is by far the most outrageous, the most camp, and truly the most beloved of the Living Dead non-Romero entries. Looking to Romero’s first sequel Dawn of the Dead (1978), which balanced Night’s scathing political satire with more cartoonish gore and laughs, Streiner and Russo update the story for 80s youth culture. It’s Night of the Living Dead on acid – featuring teen punks and outcasts besieged by ghouls. Directed by Dan O’Bannon (author of the screenplays for the Alien franchise), Return introduced the concept of zombies or ghouls craving “brains.” It contributed almost as many tropes of zombie lore as Night did in 1968. It modernized Romero’s original concepts at a time when the director was busy keeping his franchise relevant– 1985 was the same year Romero’s least successful film was released, Day of the Dead. Bannon’s Return was instrumental to resurrecting and ensuring the longevity of the zombie subgenre—its humour and punk aesthetic can be traced to more recent zombie action comedies like Zombieland (2009) and its recent sequel Zombieland: Double Tap (2019), as well as Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die (2019).

Canada had its own zombie mini-genre emerging in the 2000s with both Fido – Andrew Currie’s 2006 zombie spoof, that like Night of the Living Dead transcends its genre and seeming innocuousness to provide substantial political satire – and indie director Bruce McDonald’s Pontypool (2008), starring the great Stephen McHattie as a shock jock trapped in a station as a deadly virus consumes everyone in his town. Set in a mid-century dystopia where in the uninfected have domesticated zombies and forced them into servitude, in Fido Billy Connolly stars as the titular zombie, forced into menial chores for the nuclear perfect family “The Robinsons.” Fido forms an almost pet-like loyal bond with the family’s son Timmy, while the evil corporation Zomcom attempts to further control the population by monetize/weaponize the ever-growing zombie population and ensuing fear mongering. Fido took direct inspiration from Night of the Living Dead (specifically with its space virus origin), and like Romero’s film, Fido’s director uses a genre disguise to comment on ever-growing concerns around class and the government—albeit with a bright, flowery colour palette that is a far cry from Night of the Living Dead’s monochrome.

In Pontypool, Bruce McDonald offers a fresh spin on the zombie film while including a small rural Ontario setting (the town of Pontypool, in the Kawartha Lakes region). Much like Romero, McDonald is careful to never use the term “zombie” in his film, but rather refers to the infected with the mysterious virus as “conversationalists.” For McDonald the virus which causes humans to riot and devour each other is an effect of broken communication – the infected reveal themselves with an inability to string together sentences until eventually there are consumed by anarchy. The film revels in the claustrophobia of the radio stations confines (much like Romero did with the tiny farm house in Night) providing psychological terror that transcends gore and jump scares.

Given that Romero spent the last decades of his life in Canada – producing the final films of the Dead franchise with Canadian actors and crews – perhaps it should come as no surprise that Canada has a substantial commitment and love of the zombie genre. The internationally renowned zombie walk, which attracts thousands of participants every year was founded in Toronto by Thea Faulds (featured in the Raising the Dead’s interviews). Romero had a lasting impact on the Canadian film industry, providing countless opportunities for film students and emerging talent. Raising the Dead is a small gesture to celebrating his legacy and a projection of how important Night of the Living Dead was, is and will be down te line, especially in such uncertain times.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram