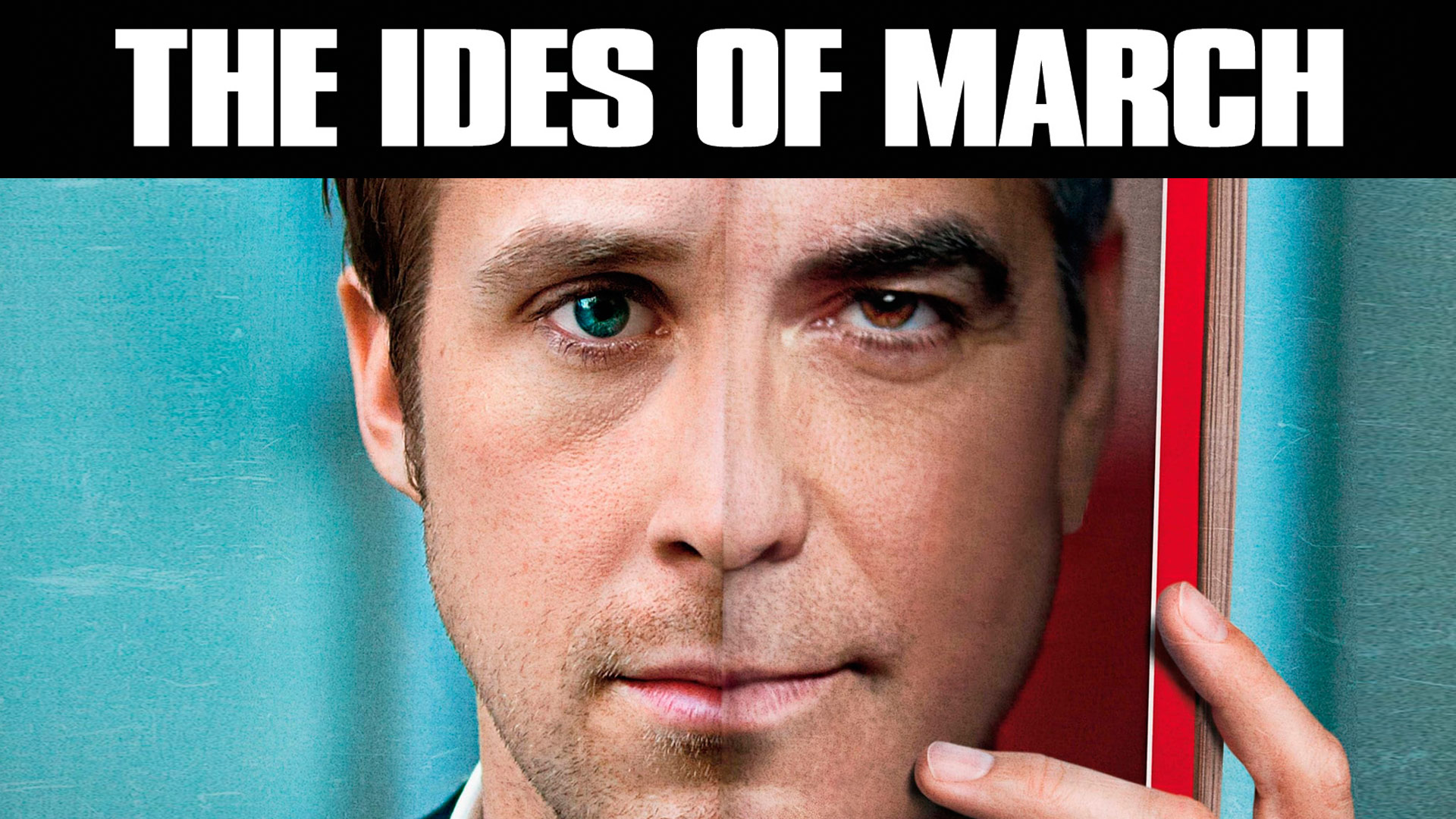

Winning Isn’t Everything: The Ides of March

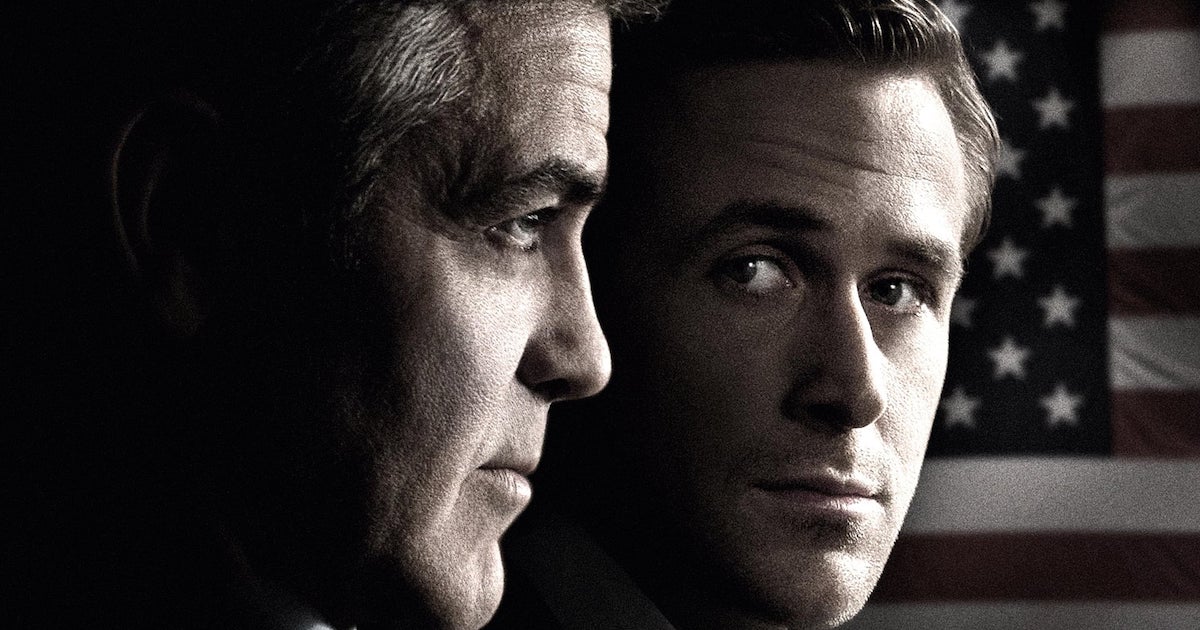

November 24, 2020 By Go BackIn The Ides of March, Ryan Gosling portrays Stephen Myers, a junior campaign manager for Mike Morris, the Pennsylvania governor vying for a Democratic nomination for US President. The savvy Myers is certain that his boss is the next great hope for America. That is until Morris’s golden boy status becomes irrevocably tarnished and Myers finds himself in a moral quagmire.

George Clooney, who co-wrote the screenplay and directed the film, also portrays Morris. He’s handsome, talented, affable, intelligent, left-leaning, and impassioned, all adjectives that could easily be applied to Clooney, so one could be forgiven for thinking that he’s just playing an extension of himself. However, there’s much more to The Ides of March than Clooney’s idealized Governor Morris and Gosling’s idealistic Myers, despite a condescending article to the contrary from Atlantic writers Eleanor Barkhorn and Spencer Kornhaber.

Presenting a numbered list of what they deem “implausible moments,” Barkhorn and Kornhaber argue that The Ides of March “should not be nominated for any award, ever.” The New York Times review from A.O. Scott is less incendiary, but not much kinder. Describing the film as “less an allegory of the American political process than a busy, foggy, mildly entertaining antidote to it,” Scott criticizes it for its inability to “connect… to the world it pretends to represent.”

The beginning of The Ides of March could indeed come across as a little too self-assured, almost like a satire of earnest people with Big Ideas. Characters speak passionately and decisively about issues, as they discuss strategies over cell phones, and from behind glass-windowed offices. You believe the things they are saying, and you believe that they believe in the things that they are saying. It’s New York Times reporter Ida Horowicz (Marisa Tomei) who comes across as self-serving and cynical. She meets up with Myers and head campaign manager Paul Zara (Philip Seymour Hoffman) at a bar for drinks, hoping to get a scoop on what’s next for Morris.

Ida accuses Stephen of having drunk the Kool-Aid, to which he agrees, insisting that “it’s delicious.” He tries to convince her that Morris is the only one “that’s gonna actually make a difference in people’s lives, even the people that hate him.” Ida scoffs, saying that it won’t matter to “everyday” people and adds, somewhat ominously, that Morris is “a politician,” one who “will let you down, sooner or later.”

Of course, Ida saying this doesn’t create the events that take place in the film’s second and third acts. Those events were set in motion well before Stephen’s life unravels. And that’s the key to understanding that The Ides of March isn’t about politics at all, but the lies we tell ourselves in service of what we believe to be the truth.

There’s an obvious parallel drawn between a couple of major narrative events in the film that are important to understand why it’s not a movie about a political race. First, there’s Stephen’s “secret” meeting with Tom Duffy (Paul Giamatti), the campaign manager for the other Democratic hopeful, Ted Pullman. Paul fires Stephen over it, not because it happened, but because Stephen didn’t tell him about it soon enough. “There’s only one thing I value in this world,” Paul tells Stephen. “That’s loyalty. Without it you are nothing and you have no one. In politics, it’s the only currency you can count on.”

The second major event takes place before the events in the movie. After a late-night tryst with Molly the intern (Evan Rachel Wood), Stephen discovers that not only did she sleep with Governor Morris, she’s also pregnant. Furious, he decides that Molly has to go away. He rationalizes this by claiming that it’s his “responsibility” to Morris, and more importantly, to Morris’s campaign. This places all the blame on Molly and none on Morris. It’s Tom Duffy who eventually exposes the fragility of Stephen’s moral high ground

Duffy admits to Stephen that he orchestrated their “secret” meeting because he knew it would remove Stephen from the game. “You work for us, great. Paul doesn’t have you. Then again, if Paul fires you and I don’t take you, fine. Paul still doesn’t have you. Either way, I win.” Aghast, Stephen tells Duffy that it’s his life he’s talking about, but Duffy insists that he takes no pleasure in it. The implication is, of course, that it’s just politics; it’s just what people do when they play the game.

Molly loses this game when she panics and overdoses on pills. It isn’t clear in the film whether it’s guilt or revenge that pushes Stephen to blackmail Morris, demanding Paul’s job as campaign manager in exchange for his silence. Either way, both men get what they want, but at the cost of Molly’s life.

The Ides of March ends much like it began, with Stephen doing a soundcheck. This time, however, he’s the one who will be on camera, not Morris. Stephen may have successfully regained his career, but he’s lost a part of himself in the process. A close-up of his face reveals it to be inscrutable. Whether he deserves a chance to win back his conscience is left up to the audience to decide.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram