Hal Ashby’s Shampoo (1975): A blast from the past

June 26, 2017 By Go Back1975 was a massive year for American movies. The top films at the box office that year would go on to reshape how films were made and distributed for decades to come. But amid enduringly popular movies and critical classics like Jaws, Dog Day Afternoon, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and The Rocky Horror Picture Show, there’s one box office-topping film that hasn’t enjoyed the same lasting appeal. Hal Ashby’s Shampoo is frequently cited as an important film, but it’s one that can take a little more work to understand and appreciate.

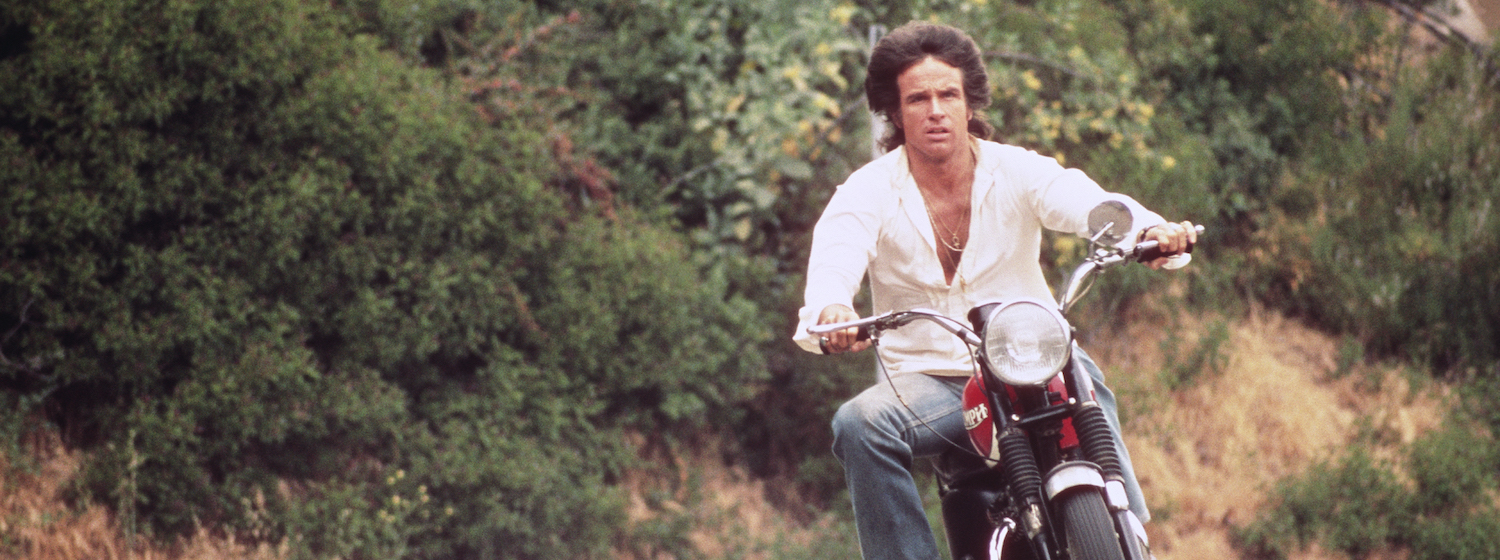

The easiest answer to why Shampoo cleaned up at the box office is its star Warren Beatty. Few were as white hot as Beatty in 1975, both as a respected actor and a sex symbol of the era. The story, which follows a lothario hairdresser and the many women he beds in L.A., seemed to mirror Beatty’s own story as a known ravenous lover on the Hollywood scene. Beatty controlled his image closely by co-writing and producing Shampoo, and is even rumoured to have had a heavy hand in directing the movie, so he was wise to the connection. Think of it as sort of the Magic Mike of its day: a hot actor choosing to openly play with his own reputation and sexualization onscreen. Add to that the fact that the film starred, not one, but two of his rumoured on-set lovers, Julie Christie (who’d starred alongside Beatty in 1971’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller) and Goldie Hawn (with whom he shared the screen in $ that same year), and suddenly the film probably seemed like a timely portal into 70s Hollywood sex and decadence.

Of course, Shampoo is more than just a vicarious trip into the life of Mr. Beatty though, even if the idea of a failing Don Juan was his inspiration. It’s his co-writer Robert Towne’s obsession with hotshot ladies man hairdressers like Jay Sebring, Gene Shacove and John Peters that give the story life. The film finds its inspiration in everything from Regency era sex farces like The Country Wife, to Moliere’s social satires, to Jean Renoir’s La Règle du Jeu, but it’s Beatty and Towne’s interest in the real men who lived their lives like this that gives the film some heft.

Robert Towne brings another trick to the table as well: His excellent sense of place and time. Just as he did in his previous hit Chinatown and his uncredited work with Beatty on Bonnie and Clyde, Towne makes plenty of hay from something that many modern viewers may gloss over: Shampoo is a period piece. Plenty of humour and dramatic irony are drawn from the fact that his post-Watergate film is set in the days leading up to the 1968 election. The free sex and drugs of sunny, idyllic 1960s Los Angeles are on full display to a world which knows those things will fade and crumble in the coming years. The soundtrack of The Beatles and The Beach Boys becomes mocking and menacing, and everything feels heightened. If this seems like a tough mental exercise, I’ll leave it to Pauline Kael to describe the feeling of the film to a contemporaneous audience:

The time of Shampoo is so close to us that at moments we forget its pastness, and then we’re stung by the consciousness of how much has changed.

Shampoo is also a platform for another great 70s talent in director Hal Ashby. Two of his most beloved films Harold and Maude and The Last Detail had already dropped that decade, and while his deep belief in relying on actors and script often mean he’s forgotten among 70s auteurs, his influence is still felt on Shampoo. While Beatty may have had a huge directorial influence, it’s hard not to feel Ashby in the visuals and editing. The pace he keeps is mostly frenetic. Tension builds beautifully, but he also allows for long, awkward humour to play out in a way that would make Larry David happy. On top of that, Ashby was always visually inventive, and here he, along with master cinematographer László Kovács, plays with the male gaze, making Beatty the deep focus of eroticism throughout the film. His hair, his wardrobe, and the way the camera trains on him takes a highly sexualized man and makes him an object in the same way he treats the women around him. Warren Beatty can be credited with plenty of self knowledge in the script, but that tense feeling of his world going off the rails as he becomes controlled and manipulated seems like Ashby had a chance in the driver’s seat.

I think with some distance from Beatty’s talents and sex life, an audience can really come to appreciate the film for its actresses and their roles in the narrative. It’s rumoured ardent feminist Julie Christie wasn’t pleased to play the “kept woman” in the film, but took the role to please Beatty. Their mutual chemistry is key to the film and they play old lovers reunited perfectly. Goldie Hawn, still fresh off her 1970 Oscar win for Cactus Flower, gets a great chance to subvert her usual diaphanous blonde image by creating someone who’s got a deeper life that’s being ignored. Lee Grant, a more veteran actress, recalls throwing herself completely into the role, and does plenty with an otherwise stock role of the libidinous and bored housewife. In fact, she did enough to win her the sole Oscar Shampoo received among its four nominations. Shampoo also provided the perfect debut for Carrie Fisher, whose foul mouthed, exacting character comes naturally. She is one of the few who sees through Beatty’s charm immediately, and is the first to manipulate him to her own ends. The role assuredly played a part in earning her next big acting gig as Princess Leia in 1977’s Star Wars, but also showcases the kind of brassy humour and bravado we’d come to love and expect from Fisher when she wasn’t saving the universe.

Shampoo can take a while to get into, but hopefully this introduction is enough to at least make you curious. Shampoo is a film that earns re-watchability by packing in nuance, great performances and insight into a period of profound change. If your first viewing doesn’t convince you, just rinse and repeat.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram