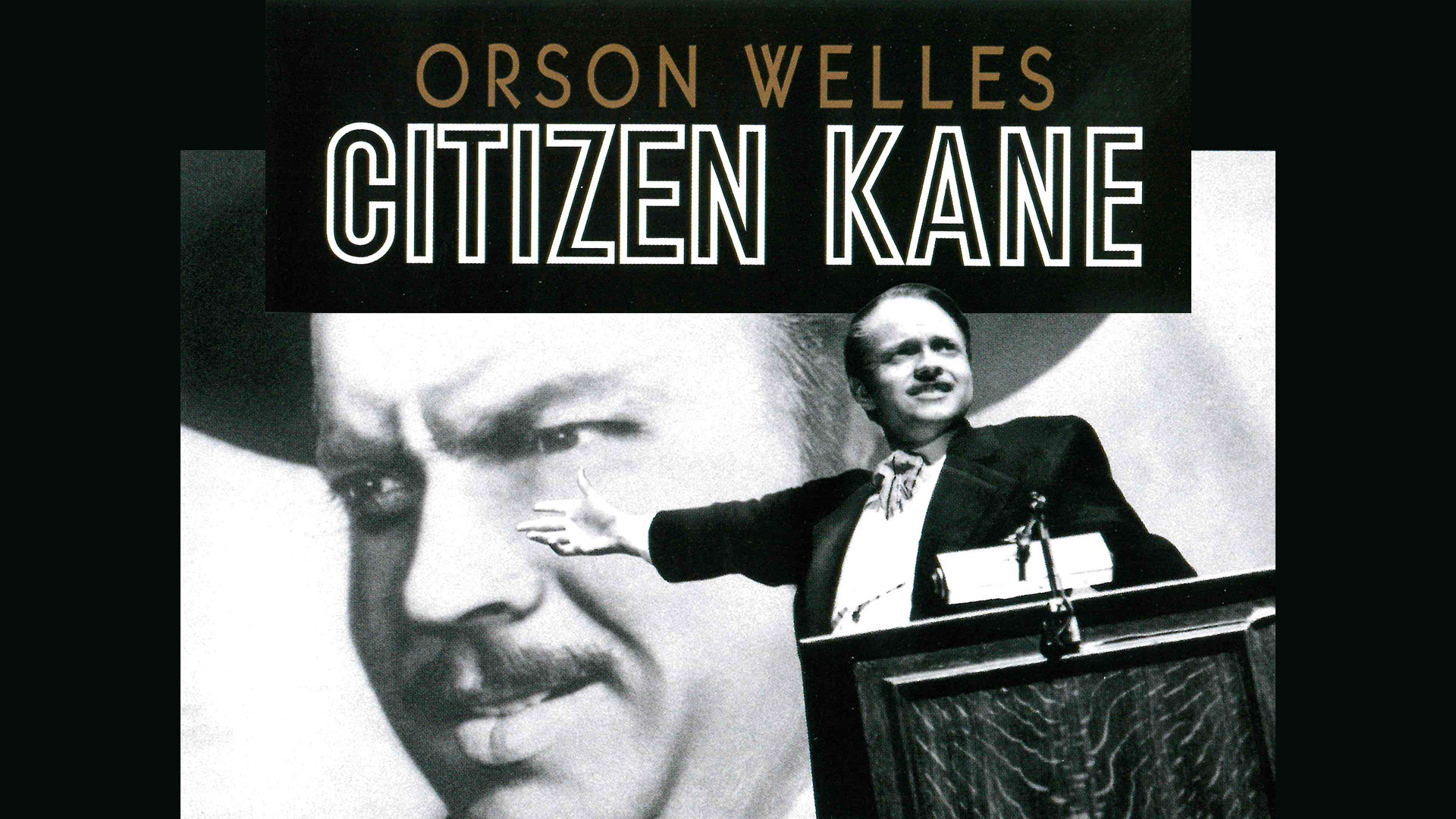

Citizen Kane: Burnt by the Sun

August 18, 2021 By Go BackThere’s a story, typically taking various forms, about how master director of photography Gregg Toland reacted when he heard that 24-year-old Orson Welles was walking around the Citizen Kane set dispensing lighting instructions — customarily the purview of the cinematographer. Rather than chasten the neophyte director on the rules, he elected just to follow him around: “That’s the best way to learn anything,” Toland apparently said. “From somebody who doesn’t know anything.”

Whether this story is true, only partly true or not true at all, it illuminates something that keys into the dazzling work that was to come: part of Citizen Kane‘s quality of overwhelming brilliance probably had to do with the fact that its director didn’t know any better. I don’t know if there’s a single other Hollywood studio sound-era movie that remains quite so vital, mysterious, alive and endlessly generous in giving. I’ve probably seen it nearly thirty times since my parents first let me sit up on a school night to catch a late-show broadcast — after which, as I recall, I was just puzzled — and I don’t think there’s been a single occasion in which something new hasn’t presented itself.

Primarily, it’s the movie’s chamber effect: it’s a story that depends as much on depth as width for its telling, and this layering aspect, manifest in both the narrative and technical strategies, can seem as disorientingly radical when confronted today as it ever was. Some of this may also originate in Welles’ radio background: space for him was as much an audio as a visual phenomenon, and the ensuing attention to echoes, overlapping sound and turbulent sonic atmospherics are consistently reinforced by the visual strategy: montages, shadows, skewed perspectives, events unpacked like books from a box.

And if the overall technical strategy was based in the sensation of depth — and Kane is nothing if not a murky, deep-end plunge of a movie — it was more than perfect for the story: of what lies behind a man’s exterior, lurks in his history, constitutes the smoke and mirrors of mythology that collect around him. True, some of this had already been articulated in German Expressionism and early film noir, but the wedding of it to the concept of all-American tragedy, the dream attained by the soul’s sacrifice, is part of what polished the diamond into such hard, permanent, prismatic brilliance. A miracle, pure but hardly simple.

Although the movie wouldn’t be what it was without key collaborators – like Toland, screenwriter Joseph Mankiewicz and compose Bernard Herrman – it was Welles who was the animating force behind the movie, the only movie in his career he had total control over. Given the legendary difficulty Welles had in getting films completed after Kane, it must have been bittersweet when the movie started to top international critics’ polls as the hands-down best movie ever made. Charles Foster Kane himself would understand. Fly too close to the sun and you get burnt. Just like that sled. But I can’t give the significance of that away. If you haven’t seen Kane, give it a whirl. It’s one masterpiece that, considering it’s eighty years old this year, still has the power to astonish.

Nevertheless, the movie became an albatross around Welles’s neck, a reminder of greatness unfulfilled, potential unrealized and faded inspiration. While there were other masterpieces to come (The Lady From Shanghai, Touch of Evil, Chimes at Midnight), Welles lived in the shadow of his masterpiece throughout his life. Which is of course absolutely unfair. Besides, if Citizen Kane were the only movie Welles ever made, we’d still be talking about it and him.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram