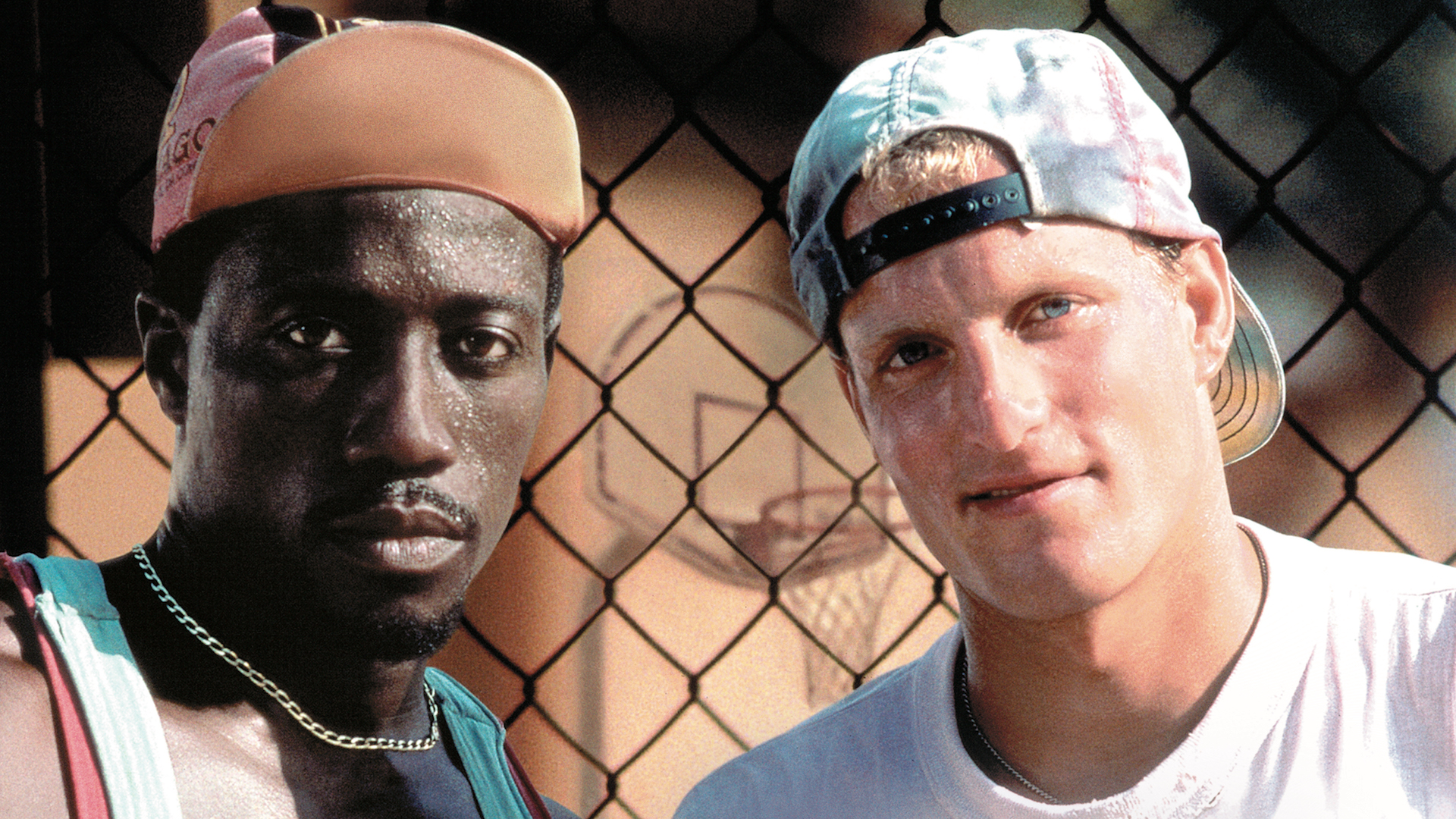

What White Men Can't Jump Got Right and Why You Should Watch It

August 8, 2018 By Go BackThough White Men Can’t Jump is a movie well remembered by those of us who were around in the 90s, it seems to have fallen out of the cultural conversation. The tale of two Los Angeles basketball hustlers played by Wesley Snipes and Woody Harrelson had a massive cultural impact from fashion to yo mama jokes, cracked the top 20 in the yearly box office, and still has plenty to give to a modern audience. Though it may be dated, in many ways it’s a unique look at a very specific place and time.

The basic pleasures of the movie are easy to understand. Wesley Snipes and Woody Harrelson, as always, are consistently electric performers able to easily flip between hilarious on-court posturing and the more serious look at struggling to get by in L.A.. Ron Shelton may not be a household name, but his work on hits like Tin Cup, Cobb, Blue Chips, Play It To The Bone and Bull Durham put him among Hollywood’s best directors of sports. His ability to shift the focus from the traditional audience perspective of sports to the athlete’s perspective shines through in all of his famous work. The movie is a joyous celebration of streetball and the unlikely friendships the court can bring, but I think the longevity of the film and the interest to a modern audience lies outside its sometimes shaggy plot and more in its depiction of Los Angeles.

Ron Shelton’s obituary will likely name him as the director of Bull Durham, but to hear Shelton tell it, White Men Can’t Jump is really his passion project and specifically, L.A. streetball is the sport closest to his heart. The vibrancy of the film shows the passion Shelton had for not only the sport but also its participants. There are plenty of wobbles in the film, but Shelton’s passion for streetball and his understanding of its undeniable link to black culture and when to step back and let that aspect speak for itself makes the film shine.

White Men Can’t Jump comes at a very specific time for L.A. between the injustice of the Rodney King beating and the explosion following the “not guilty” verdict for his assailants. The early 90s were a time that felt as if the groundswell of African-American voices in culture was unstoppable, and visible white consumption and appropriation of black culture was mainstream. It would be an easy time for a filmmaker like Shelton to make a film that imitated Spike Lee or John Singleton to ensure his success. I think White Men Can’t Jump manages to avoid crossing that line, for the most part, and achieve something more iconic thanks to Shelton not relying on just his own voice or copying others, but by closely collaborating behind the scenes with technicians and actors of colour.

The most eye-catching and memorable collaboration in the film is likely with costume designer Francine Jamison-Tanchuck. Her fantastic costumes on and off the court no doubt reflected early 90s style, but also take the extra step to be so memorable most film fans could create Sidney Deane’s cycling cap ensemble or Billy Hoyle’s mishmash of influences from memory. To take a regular character’s clothes and make them into something that can be a functional Halloween costume is pushing the fashion of a film from great to iconic. You can see her work reflected back almost a decade later when Nike not only revived the sneakers Billy wore, but also created a new pair emblazoned with quotes from the film. Between White Men Can’t Jump and her work on Boomerang (1992), it’s undeniable Jamison-Tanchuck had a hand in changing the way wider audiences, especially outside of the big cities, thought about fashion in the 90s.

A player behind the scenes whose impact extends beyond the visual was Kokayi Ampah, the first African-American in the Teamsters Union as a Location Manager and an integral part of the authenticity of the film. Shelton played all over L.A. and demanded they reflect the diversity of its neighbourhoods and Ampah managed to acquire or re-create many of the interesting courts seen in the film in their own neighborhoods. Ampah also used locations in The Jungle, Crenshaw, Watts and West Adams so the film could accurately reflect the realities and diversity of African-American neighbourhoods in L.A. Working with gangs and The Fruit of Islam to negotiate and secure locations the average Hollywood crew would fake or avoid entirely gives the film a unique flavour and presents Los Angeles in all its glory. On top of that Ampah and production designer, J. Dennis Washington tried wherever possible to build a court, refurbish a playground or use artists of colour through SPARC to create a mural that would not only visually pop in the film, but also leave something behind for a community rather than merely exploit its existence.

What many collaborators considered the most radical moves in Hollywood is minor to most viewers, in the relationship between Wesley Snipes and Tyra Ferrell, but appreciated by the participants. Ferrell recalls in her casting making a point of asking Shelton to consider a dark-skinned partner for Snipes and buck the current trend of colourism in romantic casting. On top of that, once cast, Ferrell requested the ballers improvising consider colourism in their predominantly improvised trash talk and you’ll find the film completely free of that kind of talk. Although her role is relatively small and thankless, through the fact that the film’s cast and crew listened to her opinions and respected her point of view, Ferrell managed to make the film avoid a trap its contemporaries, especially ones helmed by those outside the culture ignored or actively played into.

Once Rosie Perez outshone her counterparts (including heavy hitters like Holly Hunter and Rachel Griffiths) and got a role meant for a white woman, Shelton worked with her to create a character that felt more uniquely Puerto Rican. Perez notes the process was much more respectful and collaborative than her previous experience and her voice changed the script right down to completely re-imagining the memorable scene where Billy buys her a dress after Perez herself hated it and declared it a “hoochie” dress.

It doesn’t seem wild to listen to your actors and consider their background, or surround yourself with experienced people of colour, but plenty of films, especially in the early 90s, missed the opportunity to express their performers unique voices by being overly reliant on “colourblind” characters and a flattening of the lived reality of their films. Instead of only acting as the voice for marginalized people, the film frequently let them speak for themselves. White Men Can’t Jump throws plenty of bricks when it comes to its exploration of race, but the fact that filmmakers went out of their way to present their setting authentically, truly loved what they were showing, reflected the vibrancy of the local culture and allowed collaboration with the community around them make this film more than a tone-deaf capitalization on black culture. The film’s legacy was quieted, mostly by studio malaise after Shelton won a groundbreaking lawsuit for profits, but has plenty modern audiences can appreciate. Any movie that’s good enough to be among Stanley Kubrick’s favorites and was permanently memorialized in a Venice Beach mural at least deserves a second look.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram