Jack in the Box: The Shining at 40

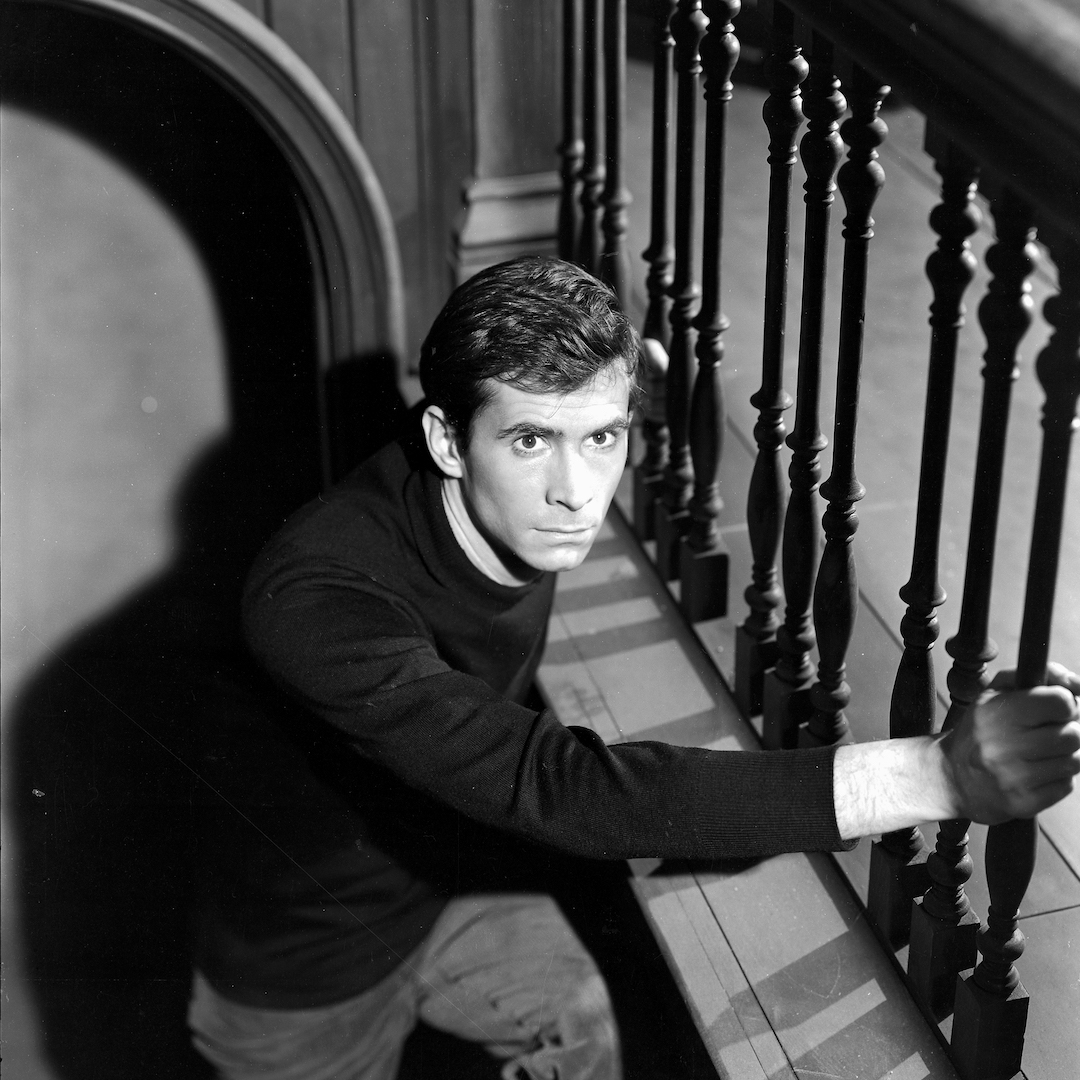

October 5, 2020 By Go BackThe most meticulously scrutinized horror movie since Psycho, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining landed with something of a dull thud when it opened the summer of 1980.

Expectations were high. Stephen King’s source novel – about a family wintering alone in a diabolically haunted, remotely situated hotel – was a bestseller, Kubrick’s reputation firmly established, and the very idea of this director filming this author’s work intimated something profoundly scary was on its way. It didn’t hurt that the production had been surrounded by Kubrick’s customary wall of secrecy.

But it wasn’t scary, at least not in the jump-out-go-boo sense. It was a movie that traded far more in atmosphere than mechanical fright effects, and equally more in calculated disorientation strategies than coherent plot.

Indeed, on certain levels the movie seemed pretty much senseless: you could never tell if the visions plaguing alcoholic author Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson in full kabuki mode) were real or imagined, or if the remote, snowbound Overlook Hotel was actually a malevolent and haunted place or if everything Jack saw was the product of his tortured and thirsty imagination.

Case in point: the scene where Jack, now more or less fully unhinged after months of isolation at the Overlook, looks down on the table-top replica of the hotel’s intricate maze and sees his son (Danny Lloyd) and wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall. walking through the maze. How could this be? At this point, any security we might have taken from the apparent boundaries between objective reality and imagined delusion were completely erased and defiant of coherent explanation. No wonder the movie was met with such disappointment and confusion when it first appeared.

(Personal note: when I first saw it, I was a relatively recent Stephen King fan and a long-time lover of Kubrick. I, like dozens of critics and reviewers, just found the movie baffling and disappointing. What was this? A horror movie or a comedy? A haunted house movie or a deep psychological plunge? Reality (in movie terms) or pure, psychopathic delusion? I’ve since seen it more times than I can remember and consider it something of a masterpiece. Plus I no longer read Stephen King.)

Appearing at the dawn of the home-video era, The Shining began its gradual reputational rehabilitation when people could scrutinize the movie as closely as Jack glared down at that maze. Only then was the extent of Kubrick’s elaborate design truly apparent, and only then was the movie’s own maze revealed. And this, more than anything, accounts for how The Shining managed to be both unsettling but in no way shocking, and objectively senseless but psychologically true: it put you inside the fevered head of Jack Torrance, and that wasn’t necessarily a comfortable (or coherent) place to be.

Parsing The Shining is itself such a maze-like activity that it has inspired its own feature-length documentary, Room 237. Highly recommended to anyone who has even mildly obsessed over the movie’s meaning (or, maybe more accurately, meanings), Room 237 provides room for a number of amateur forensic voices to hold forth on their interpretations of the movie, accompanied generously by clips that, to a truly fascinating and surprising extent, seem to bear even the most outrageous theories out. (Among others, that Kubrick helped fake the Apollo 11 moon landing.) Another sign of just how intricately the movie is deliberately designed. Again, think of Jack Torrance peering down at his family on the table-top maze.

(Other supplementary viewing must include the documentary on the film’s making shot by Kubrick’s daughter, which provides the most extensive film record of the director’s working methods available. Also worth watching is last year’s Doctor Sleep, director Mike Flanagan’s adaptation of King’s recent sequel to The Shining. A fine achievement in its own right, the movie also manages to pull off this mean feat: finding the middle ground between King’s plotting and Kubrick’s visual style without sacrificing its own integrity as its own considerable achievement.)

King hated what Kubrick had done. He was especially offended by the movie’s unfathomable tone of a waking nightmare, and especially pissed that the director had scuttled the book’s scenes of killer topiary in favour of that giant maze. Years later, in fact, King would be heavily involved in a more literal TV adaptation of the book, but by that time Kubrick’s film had already undergone its rehabilitation to the status of contemporary classic.

While some of the fan theories spun over the course of Room 237 stretch credulity, they are testimony to a movie which compels multiple viewing and interpretations. I suspect one either watches it once – frequently in confusion or disappointment – or over and over again. Like the maze which so angered Stephen King, The Shining is a kind of labyrinth one enters, only very rarely providing a bird’s-eye view of the big picture. (Indeed, as Room 237 makes clear, the layout of the hotel itself defies logic.) It’s a trap, of sorts, or maybe one of the most elaborate jokes in movie history. One thing it shares between its viewer and protagonist is this fact: once one has entered the movie or the hotel, it’s almost impossible to find your way back out.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram