The Blob(s) Are Going to Get You: Comparing the Original to the Remake

March 3, 2020 By Go Back“Beware of The Blob, it creeps

And leaps and glides and slides

Across the floor

Right through the door”

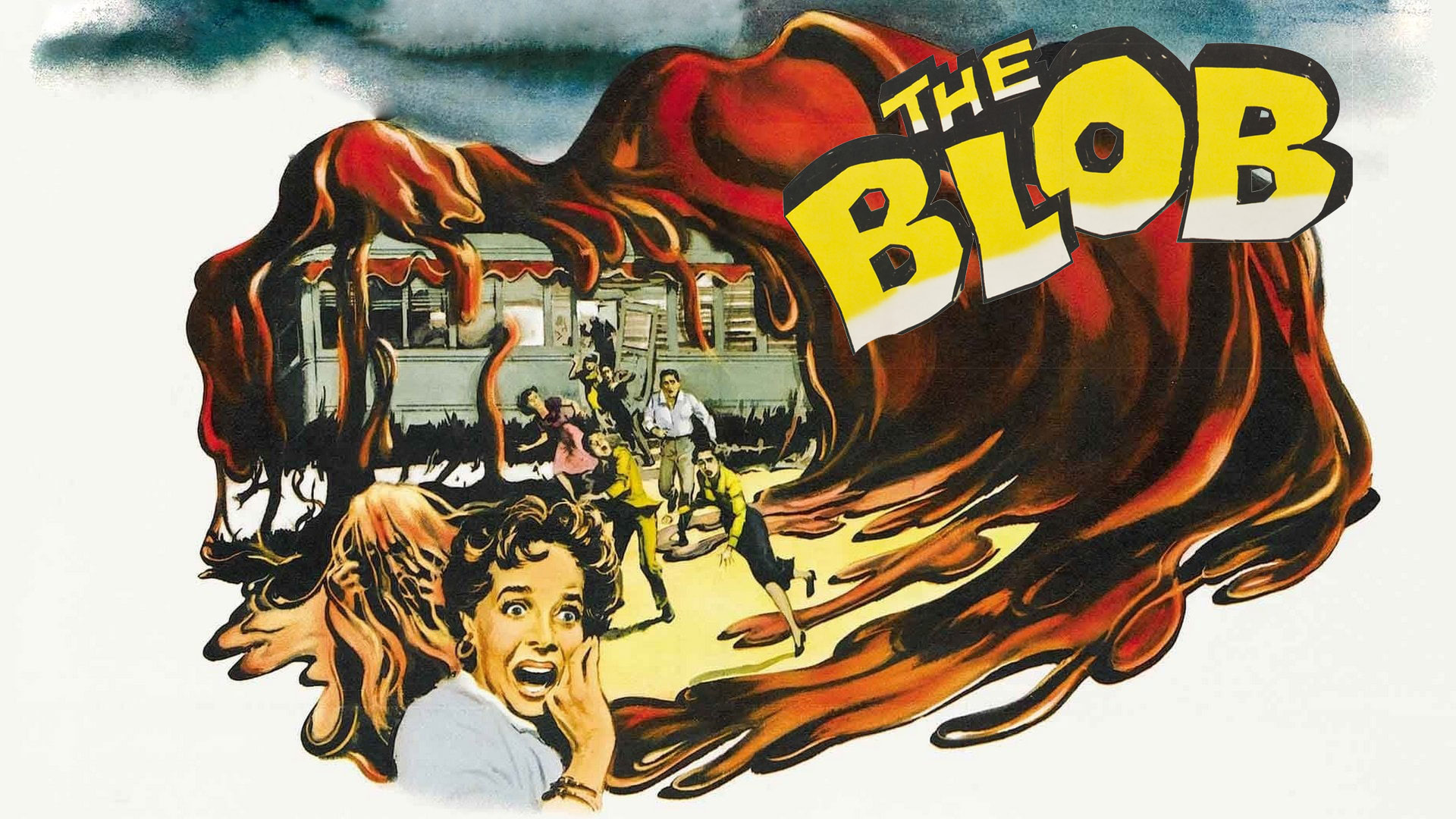

From the film’s opening title sequence, with a catchy jingle sung by the fictitious band “The Five Blobs,” the original 1958 version of The Blob readies viewers for more of a romp than a horror film. The song, with its cartoonish lyrics and bossa nova beats, serves as a red herring to a film that would offer up terror, suspense, and gore to mid-century audiences. A few years before Hitchcock’s Psycho, The Blob was the reigning horror film of the 1950s midnight movie crowd – a low budget B-film that became wildly successful, and an unprecedented hit at movie theatres, drive-ins and later on television. It was such a lucrative property, so iconic and ubiquitous that thirty years later it was remade – but where ethos of the 50s ruled in the original, the 1988 version would issue forth very different politics.

Produced independently by Jack H. Harris and directed by future theme-park designer (and tele-evangelical producer) Irvin Shortess “Shorty” Yeaworth Jr., 1958’s The Blob first came to life as a project titled “The Molten Meteor.” Designed to be paired up as a double feature (it would be distributed by Paramount with I Married a Monster from Outer Space), it was eventually retitled “The Glob,” until a children’s book with that name was unearthed, and producer Harris and screenwriter Kay Linaker settled on The Blob. And while the film’s lead Steve McQueen is today considered one of the biggest stars of the subsequent decade, he was a relative unknown at the time of his casting.

The Blob opens with a meteor crashing to earth – a trope that places it firmly within the genre of science-fiction. When a gooey substance emerges from the meteor and attacks a farmer, consuming his hand and later the entirety of his body, the real horror components of the film emerge. Throughout the film it’s up to McQueen’s character and his friends to convince authorities (the town’s doctors, the police, even their parents) that something terrible is to befall their small town. Understandably, their description of a pink Jell-O-like gooey substance that devours everyone in its tracks rings preposterous, and McQueen’s character is forced to reckon with the alien being’s deadly potential. Only when the blob attacks a full movie theater does the town realize the danger it’s in.

Filmed far from the Hollywood studio backlot, The Blob utilized rural Pennsylvania for its shooting. Most sequences were filmed in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania at Valley Forge Studios – an organization that had produced over 250 religious films. A fitting home, given that the film’s director, Shorty Yeaworth as well as the film’s co-writer Theodore Simonson were Methodist Ministers. For the film’s iconic movie theatre climax, production moved north of Philadelphia to Phoenixville and its Colonial Theatre, a historic building still standing and still in operation that dates to 1903 (it’s currently the site of the annual Blobfest). Movie culture is key to the appeal of The Blob. There’s something magical about sitting in a cinema, watching a doppelganger audience get devoured by an anomalous monster. Producers of The Blob were detailed in their approach for the movie theatre climax, populating the Colonial with recognizable, real-life elements of movie promotions – such as a slightly altered (so as to not infringe copyright) poster of MGM’s Forbidden Planet (1956), as well as one for the Harris-produced Vampire Over London (1952), the latter, a fellow B-film starring an aged Bela Lugosi.

The producers of The Blob knew the film was hinged on its special effects, for which the corresponding budget was low (the entirety of the production budget was a meagre $120,000 US). To achieve The Blob’s effect, they employed silicone mixed with red vegetable dye, as well as some balloons covered in bloody goo (both of which rendered gloriously in DeLuxe Color, a lower budget competitor to Technicolor). The constraints of the budget seemed to dictate simplicity and fast-thinking – sometimes going without (in this case a Hollywood practical effects team) produced remarkable results. If the film’s special effects look rather rudimentary by today’s standards, the fact is that they were highly effective in 1958, an era of movie making where monsters were mostly men dressed up in rubber suits. The materiality of The Blob and its uncanniness seemed to captivate audiences. Coming in $10,000 under budget, it did a lot with very little, unlike its remake thirty years later.

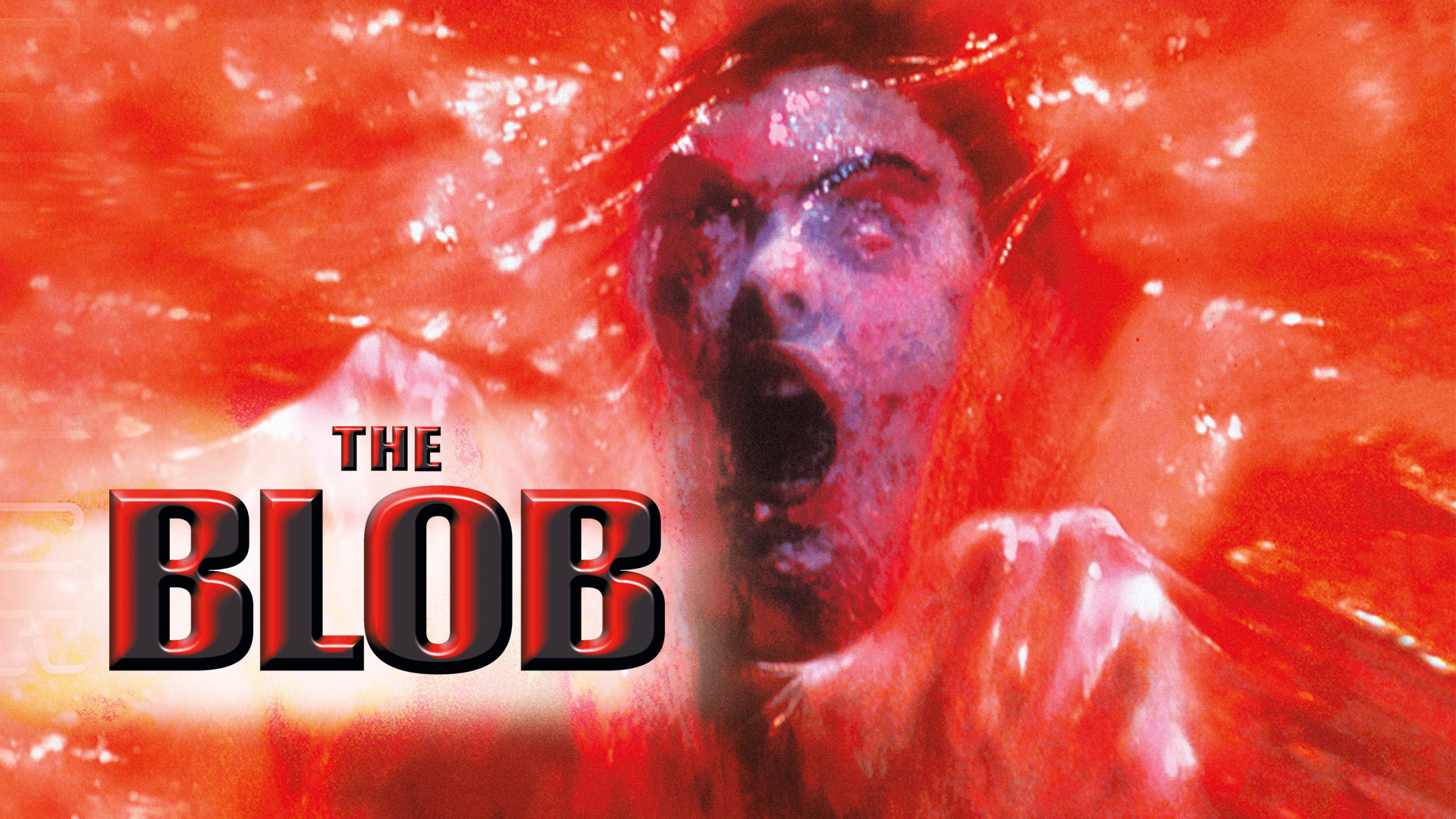

By the late 1980s, The Blob was firmly entrenched in the horror canon. A certified B-film transformed by A-film box office. When it came time to remake it, director Chuck Russell sought out his former collaborator (on 1987’s Nightmare on Elm Street 3) screenwriter and future director Frank Darabont. Darabont brought a distinctly Stephen King feel to the remake’s screenplay – King had found inspiration for his stories (and later his screenplays and directed films) from the 1958 version of The Blob – so Darabont and Russell’s work on the screenplay was a confluence of sorts. Where the budget for the original was modest, the budget for the remake was quite substantial – $19 million, with $9 million earmarked for special effects alone. It goes without saying that movie special effects had hugely progressed over those thirty years, yet when it came to recreating the blob, effects supervisor Tony Gardner resorted to organic materials as utilized in the original version of the film (in this case silk strands injected and dyed with a common food additive). And while the effects look polished and quite impressive even by today’s standards, the film was a total box office bomb, earning back less than half of its budget.

Why might this be? The Blob remake when viewed today is campy, slick and delightfully twisted. It’s certainly gorier and extremely violent (killing off one of its main characters in the first act just for the shock value) and, just like its predecessor, it’s considered a cult classic. But whereas with the original audiences instantly connected with the thinly veiled metaphor of the Red scare (i.e. The blob, in its ability to devour all in its wake and consume everything in its path, threatening middle-American homogenous values), the remake had a distinctly less uniting politic. In 1958, communism was feared by all, as dictated by the American government – all outsiders posed a threat and the greatest cure to this was conformity, especially as it pertained to America’s youth. When McQueen’s character is bullied by his fellow teenagers at the beginning of the film, it’s up to him to turn them around, to befriend them rather than rebel or antagonize. In the 1988 version, however, the teen hero played by Kevin Dillon is distinctively an outsider, a friend to no one and a menace to authorities from the very beginning.

While a meteor crashes to Earth precipitating the blob’s appearance, just as in the original, the mayhem that ensues has a different origin in the remake – not the alien being itself, but the American government as it attempts to harness the blob’s power as a weapon. The remake is less a sci-fi horror and more of a conspiracy theory film, coming at a time when faith in the American government was at an all-time low, a result of the post-Vietnam, post-Watergate era. The 1988 version was prescient in many ways, as discussions of the ethics and ramifications of developing biological weapons for war with the middle east was recurrent in the media. If the Eisenhower-era audiences of 1958 were fine with the idea of the enemy being a foreigner, the Reagan-era audiences for the remake may not have wanted to look at themselves in the mirror. The difference between teenage baby boomers at the box office and their kids was less about polished special effects or genre, and more about how they saw themselves reflected. The good guys, like McQueen’s character in the 1958 version had grown up to exert some concerning threats by 1988. Watching the two Blobs is like watching a before-and-after of American values, of the country’s fears, and of how youth culture was portrayed. Like how The Blob was designed to flesh out a double bill, the two versions watched back to back offer viewers an interesting experiment in how the same story can take on such different meanings.

Find the next playtimes for The Blob (1958) on Hollywood Suite.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram