Popeye: The WTF Masterstroke in Robert Altman’s Filmography

January 5, 2018 By Go BackAwarded 1980’s Worst Picture by the Hastings Bad Cinema Society, Popeye – Robert Altman’s musical adaptation of the beloved Depression-era comic strip and animated cartoon – is an enigma. A divisive film that signalled, if not epitomized, a major slump in the career of a master filmmaker, Popeye held immense commercial appeal, yet in the hands of a director who played by his own rules, it was destined for failure. While Popeye is persistently cited as a canonical box office disaster, that label is somewhat misattributed. Its box office revenue was healthy and its subsequent home video popularity turned considerable profits for its studios. Yet it was labelled a box office bomb because its intentions were out of step with what an independent, iconoclastic director like Altman had previously produced – it was also a Disney film, so expectations were high to say the least. That Altman could make a comic-strip adaptation featuring Robin Williams outfitted in prosthetic arms and a gaggle of oddly-shaped performers and completely reject camp is miraculous. If one film attests to Altman’s singularity, it is Popeye.

A groundbreaking co-production between Paramount (who owned the Popeye character) and Disney (in the midst of their own 1980s slump), Popeye was conceived as a competitor to Columbia Pictures’s optioning of the Broadway musical hit Annie. The pairing of Altman and Disney is perplexing to say the least. An omnivore when it came to genres, he had nearly tried his hand at them all – war (MASH); the western (McCabe and Mrs. Miller); film noir (The Long Goodbye); crime (Thieves Like Us); comedy satire (Nashville) – and had experienced considerable critical success. By the time Nashville was released in 1975, Altman was a bona fide New Hollywood pioneer – an American auteur of unique branding. Post-Nashville, however, Altman experienced a popular backlash. While 3 Women (1977), and two subsequent late-70s releases garnered critical acclaim, they were financially fraught productions and releases. When the producer of Popeye Robert Evans shopped around for a director – having initially thought of Hal Ashby, Arthur Penn, and Mike Nichols for the project – Altman jumped at the offer when approached, which, given his track record, is strange to say the least.

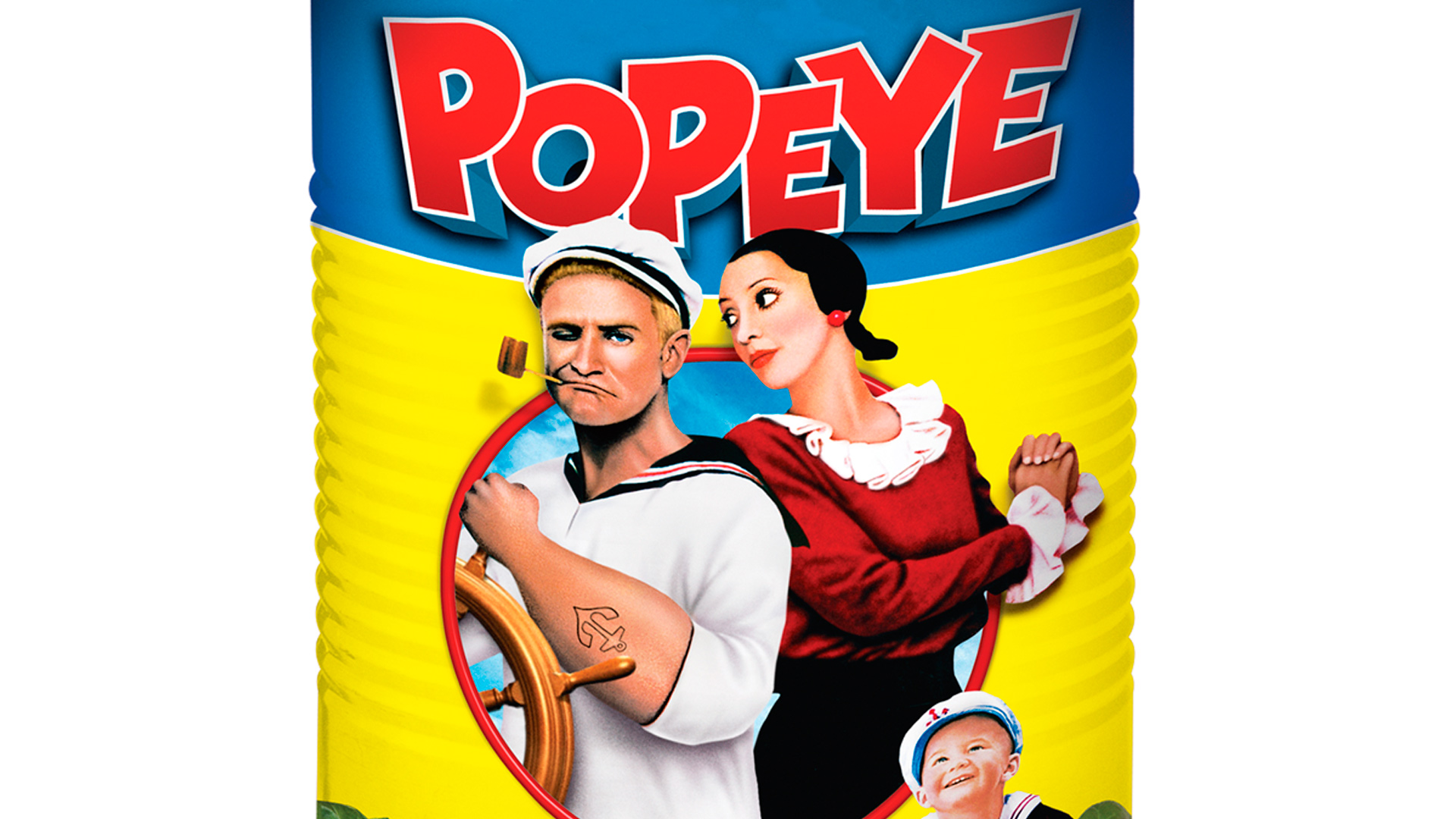

Even though this was a big studio production, Altman was going to direct it his way – his choice of actors, his locations, his style of eliciting empathetic performances. The studios wanted Dustin Hoffman and Lily Tomlin to star, but newcomer Robin Williams – fresh off his Mork and Mindy stint – was perfectly cast in his feature film debut. And while Altman had worked with Tomlin to great success in Nashville, how could Shelley Duval not have been cast as Olive Oyl? The svelte, otherworldly actress was Popeye’s love interest incarnate (the actress admitted to being called Olive Oyl in grade school). When filming began in Malta, Duvall had recently completed The Shining (1980). Her trauma at the hands of Stanley Kubrick was channeled into her fragile, sublime performance as the frantic, acerbic, yet loving paramour. Altman even cast his own infant grandson as Popeye’s adopted son Swee’Pea. With the cast rounded out by the burly Paul L. Smith in the role of Bluto – Popeye’s nemesis and Olive Oyl’s cad – Altman had created his own cartoon universe, complete with stunt performers drawn from San Francisco’s Pickle Family Circus (the influencer of Cirque du Soleil) comprising Sweethaven’s townspeople.

Filmed on the remote archipelago of Malta, and with Federico Fellini’s frequent cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno behind the camera, Popeye was a bit of a film production nightmare. Williams referred to the set as a “stalag” (a German prisoner-of-war camp). To build Sweethaven, a 165-person construction crew worked tirelessly for seven months, building nineteen structures along edge of the Mediterranean Sea on docks and perched on cliffs (you can visit the set today, as it lives a second life as Popeye’s Village, a family-run amusement park in Anchor Bay). The studios imported lumber from the Netherlands and shingles from Canada. 2000 gallons of paint were utilized, as well as 7000 kilograms of nails. It was an endeavour – one that should have sent up red flags for the producers. Altman wanted to get as far away from Hollywood as possible to make this film, intent on keeping his creative decisions his own and his production far away from any possible visiting producer or studio exec. The Malta location adds a bizarre, gritty feel to the film. Colourless except for splashes of the ocean’s green-blue hues, it looks like a nightmare of slivers and tetanus. The set is similar to the one Altman constructed in British Columbia for McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971) – the turn-of-the-century Pacific North-West western with a brothel at the centre of its drama. McCabe and Mrs. Miller is an undisputed masterpiece. There is one genius nod to it in Popeye, with Altman taking the sailor-man and the Oyl family to a Sweethaven brothel in search of Olive’s brother Castor – a prostitute reclining while smoking opium and gazing into the mirror is a call out to Julie Christie’s final scene in McCabe.

In many ways, Popeye is like a McCabe and Mrs. Miller for the family set (even with Sweethaven’s prostitutes and Popeye’s frequent swearing). A PG-rated film about a band of derelicts and unsavoury characters, with a loner hero finding his admirable equal in a capable and defiant woman. Where McCabe had an iconic score from Leonard Cohen, Popeye relied upon the 70s troubadour Harry Nilsson (of “Without You” fame) – who, taking a break from his studio album, wrote Popeye’s soundtrack on a reported drug-fuelled bender. The songs, for the most part, are baffling. Yet, Altman isn’t really directing a musical, as much as he’s utilizing music to pepper Popeye’s universe. The songs are not meant to be catchy – as the film’s introduction with “Sweethaven: An Anthem” will attest. The songs are less pop and more circumstance. They build Sweethaven to be more than it appears. Dark, brooding, and gritty – this isn’t a comic strip come to life, as much as it’s a series of comic book characters dropped into the depressing realities of life. And while the songs somewhat fizzle, there is a major exception: Olive Oyl’s painfully beautiful reverie “He Needs Me.” Sung by Duvall, it’s the highlight of the film, and one of the iconic actress’s most sincere triumphs. It’s a sequence that has held great influence on a subsequent generation of American directors – growing up on Popeye, Paul Thomas Anderson paid homage to Duvall’s loving, timeless anthem in Punch-Drunk Love (2002).

Popeye fans were disillusioned with Altman’s manic vision of a revisionist widescreen musical spectacular. With the story based more on Popeye’s original source material – E.G. Segar’s “Thimble Theatre” comic strip from the 1920s – and not on the more recognized fiction created by the Fleischer Brothers for their Popeye cartoons in the 1930s and beyond, misplaced dismay was to be expected. Popeye didn’t even like his spinach in Altman’s version (a trope from the original comic strip). Audience fury aside, Popeye is a fascinating work. Comic strip adaptations were fraught, with 1968’s Barbarella fizzling a decade earlier and Flash Gordon – released the same year as Altman’s work, and based on another property from Popeye’s original publisher – being modestly successful but generally laughed at for its theatricality and gaudiness. Both Barbarella and Flash Gordon are cult classics today – and it would appear that recent Altman reappraisals would place Popeye there soon enough if it’s not already firmly entrenched in its cult status. Like the ships sunk by the Maltese crew, Popeye capsized the director, and his slump would continue until the early 90s, when The Player would issue forth an Altman Renaissance. Popeye is, somewhat ironically, one of his most recognized works, albeit for the wrong reasons. And given the recent slew of derivative comic strip adaptations, why not revisit one of the most notorious adaptations in film history? It will likely surprise you.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram