Norman Jewison: How a Toronto kid took over Hollywood

November 16, 2021 By Go BackTune in to Hollywood Suite November 19–21 for Norman Jewison Weekend, a celebration of the iconic Canadian director’s legendary career!

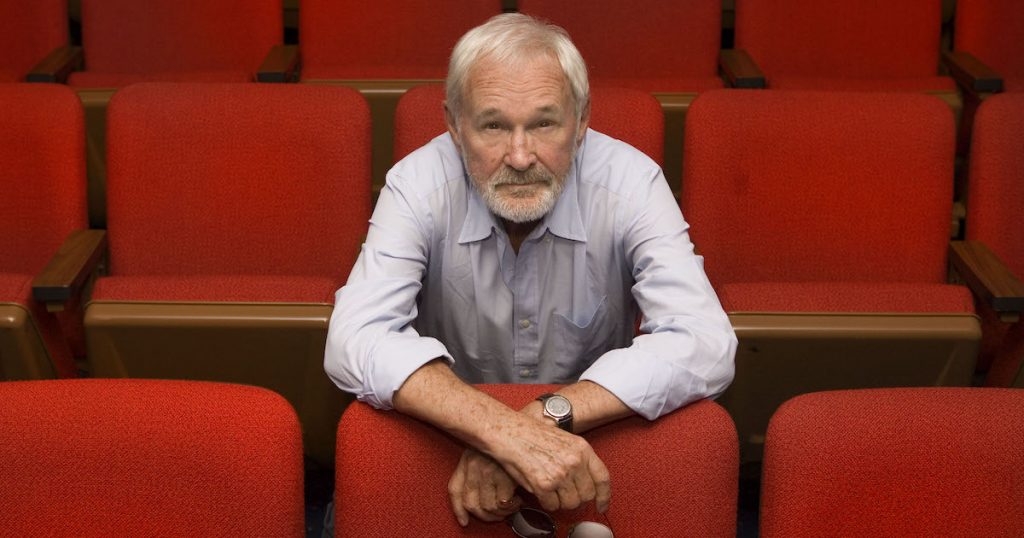

When I set out to write the first biography of film director Norman Jewison, I hoped to solve a mystery. Born to a middle-class family in a rough part of Toronto in 1926, Jewison did not enjoy what you’d call a “privileged” upbringing. After a stint in the Canadian navy and graduating from university, Jewison had few solid career prospects. In the early 50s, he was driving the night shift for Diamond Cabs. A decade or so later, he was directing Tony Curtis, Rock Hudson, and Doris Day, some of the biggest film stars in the world.

Hence, the mystery: how does a kid growing up in Depression-era Toronto, with zero industry connections, become a major Hollywood film director? How did Norman Jewison happen?

I’ll share my hypothesis. But first, another mystery. After Norman Jewison beat the odds and went on to direct so many iconic films, why wasn’t he more famous? Like, Spielberg famous? Consider the filmography: The Thomas Crown Affair, Fiddler on the Roof, Jesus Christ Superstar, Rollerball, Moonstruck, the Hurricane. Film buffs remember 1968 as one of those epochal years at the movies, with The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? all up for best picture. The winner? In the Heat of the Night, Jewison’s hard-hitting, Civil Rights-era drama.

All told, Jewison’s 24 films garnered 46 Academy Award nominations over four decades. He stands with Spielberg, Alfred Hitchcock, and Walt Disney as a winner of the Academy’s Irving G. Thalberg award for lifetime achievement.

As the great screenwriter William Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Princess Bride) once said, Jewison was a “giant of the industry,” and yet Jewison, like Sidney Lumet, “could walk down any street, in any city in the world, and no one would know who they were.” Some said it was because he cared more about the films than about his own brand. Some said it was because he was Canadian.

The real reason, I think, is because each of his films are unique. Audiences loved his science-fiction bloodbath Rollerball, and audiences also loved his thoughtful character study about a nun, Agnes of God, but they probably weren’t the same audiences. A “Norman Jewison” film wasn’t predictable product. For early devotees of the “auteur theory”—who believed that the mark of a great director was a consistent visual signature—Jewison’s eclecticism was hard to compute. Looking back, however, Jewison’s vast directorial range seems more like a testament to his staggering talent and sheer lust for the full range of human experience.

Consider the diversity of films on offer this Norman Jewison Weekend. The Russians are Coming, The Russians are Coming, is in some ways classic Jewison, in which the director smuggles a serious message (about the insanity of international conflict in the Cold War) into a madcap comic romp featuring Carl Reiner, Jonathan Winters, Tessie O’Shea, and Alan Arkin (originator, I am convinced, of Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat accent). Critics hailed Russians as the most hilarious film of the year (one complained that “the dialogue is occasionally smothered by the screams of merriment from the audience”), while a U.S. Senator moved that a laudatory review be printed in the U.S. Congressional Record, which it was.

In the Heat of the Night was something else entirely. Heat, about a Black detective forced to solve a murder in a profoundly racist Southern town, is “so f***ing revolutionary we don’t realize it now,” according to star Sidney Poitier. While making the film, cast and crew stayed at the Holiday Inn in Dyersberg, Tennessee—the only hotel that would accept Black people. Heat was enriched by contributions from editor Hal Ashby (Jewison’s protégé, who would go on to become a major director in his own right), and cinematographer Haskell Wexler, who brought a gritty, documentary-like visual sensibility to the material.

Jewison, who marched in Martin Luther King Jr.’s funeral procession, is a lifelong anti-racist committed to bringing more Black stories to the screen. It was often a struggle. The virtually all-Black cast of A Soldier’s Story “was just an absolute turn off” for the major Hollywood studios in the early 1980s, Jewison remembered. He eventually got the film made by offering to work for free. A Soldier’s Story, a complex portrait of racial reckoning wrapped in a gripping murder mystery, became a sleeper hit, with electric performances from Adolph Caesar and Denzel Washington.

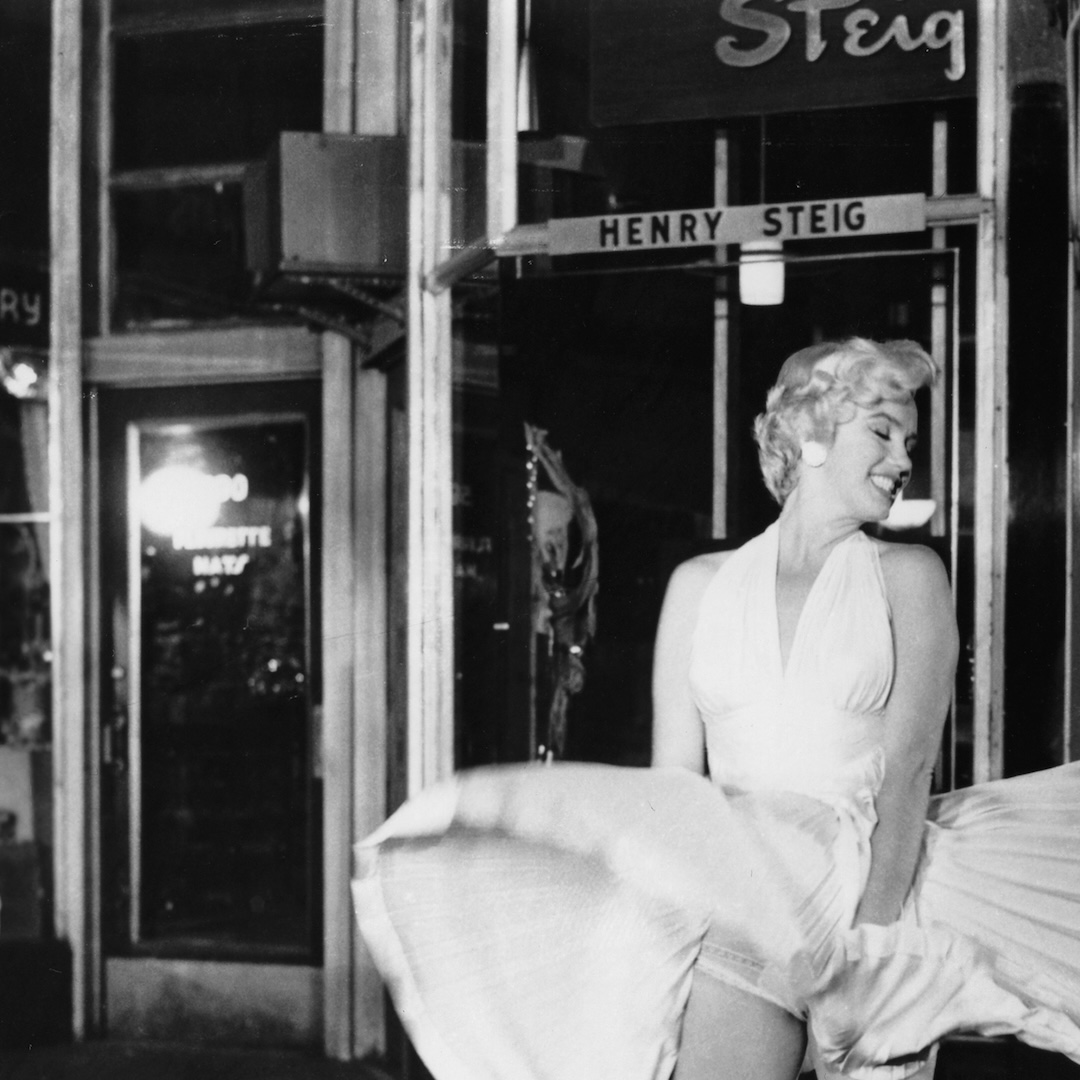

But Jewison contains multitudes, and for every hard-hitting racial drama, it seemed, he also produced a whimsical romantic gem. Moonstruck, Jewison’s quirky ode to the madness of romantic love, has been having a moment: in the depths of the COVID-19 lockdown, Vulture declared that “Moonstruck is the Morbid Spaghetti Rom-Com We All Need Right Now.” Only You, Jewison’s homage to the William Wyler classic Roman Holiday, has emerged as a cult favourite in recent years. Jewison felt that Marissa Tomei was uncannily reminiscent of a young Audrey Hepburn—see if you don’t agree.

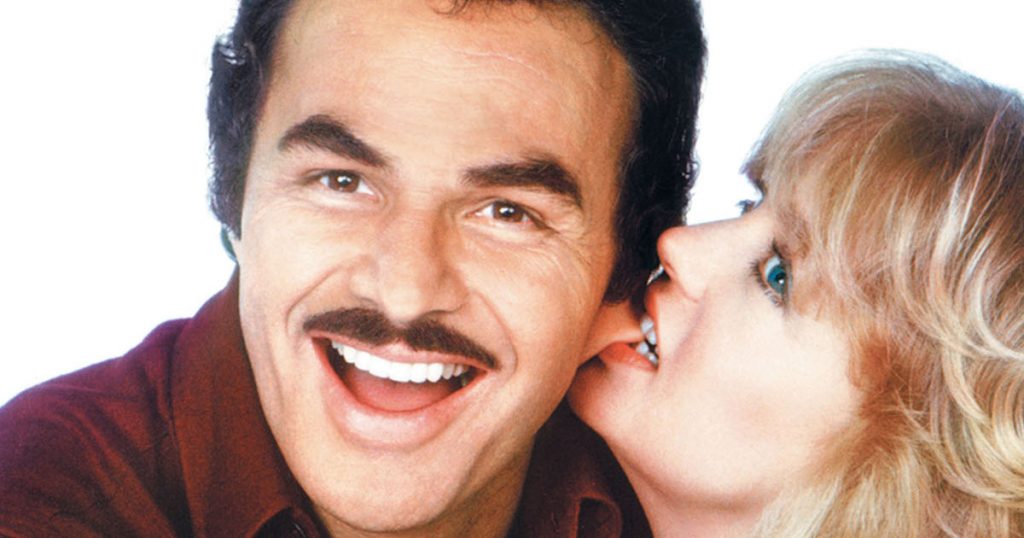

Then there is Best Friends, a cinematic parent of Meet the Parents, structured as an upside-down romantic comedy: when we meet Goldie Hawn and Burt Reynold’s characters, they are already in love—it’s marriage itself that gets in the way. Best Friends may be Jewison’s most under-rated film. Roger Ebert adored the film, especially Hawn and Reynolds’ performances: “this becomes a movie filled with moments in which we recognize not movie stars,” Ebert said, “but ourselves.”

Hawn loved working with Jewison: “There’s no aggression in him,” she said. “He’s all love.” Reynolds called him “the nicest director, maybe, in the history of Hollywood,” before conceding, that “‘nice’ doesn’t explain anything about the career, does it? He must be able to kick the s*** out of people in meetings.”

And that, I think, goes a long way toward explaining the mystery of Jewison’s astounding success. He could be all supportive, compassionate, fatherly, “all love”—but he could also be relentless when fighting for his vision. He modulated his own performance as a director according to the psychological needs of those around him. Above all, he was possessed of a truly astonishing drive.

Now 95, Jewison has lived an improbably full and fascinating life. His movies, too, are preternaturally full of life, brimming with hope, tragedy, humour, heartbreak, and joy. The films may be incredibly different, but Jewison’s spirit manages to unite every frame.

Ira Wells is an assistant professor of literature at the University of Toronto and author of Norman Jewison: A Director’s Life.

Norman Jewison Weekend November 19–21

Friday, November 19

The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (1966) 9pm ET on HS70

In The Heat of The Night (1967) 11:10pm ET on HS70

Saturday, November 20

Best Friends (1982) 9pm ET on HS80

A Soldier’s Story (1984) at 10:55pm ET on HS80

Sunday November 21

Moonstruck (1987) 9pm ET on HS80

Only You (1994) 10:45pm ET on HS90

All titles available on Hollywood Suite On Demand all month long in November. Select titles above for additional playtimes.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram