Boy Meets Girl, Bullets Fly: How Bonnie and Clyde Changed Everything

February 12, 2019 By Go BackIf Jack Warner had had his way, nobody would have seen Bonnie and Clyde and pop cultural history as we know it would tell an unrecognizably different tale. But by 1967, Warner, one of the last remaining moguls from the classical studio period, was up against two formidable forces he simply couldn’t deny: Warren Beatty and the 1960s. Warner allegedly went to his grave loathing the project, which by all accounts changed the history of American movie-making.

“There’s so much about this movie that people tend to hyperbolize. The real stories – they’re even better.” — Warren Beatty.

Warner was hardly alone. After premiering at the Montreal Film Festival, the cast and crew of the movie – an unapologetically loose re-enactment of the Depression-era crime spree perpetrated by two Texan lovebirds John Dillinger once accused of “giving bank robbers a bad name” – received fourteen thunderous curtain calls. Beatty, who had nurtured the project since it was originally slated to be directed by the French New Wave wunderkind Francois Truffaut, was convinced his baby would finally be permitted to enter the world triumphantly. But it wasn’t to be. Nonplussed by the Montreal reaction, Warner maintained a policy of limiting the film’s release and burying it old-school like an orphaned B-movie.

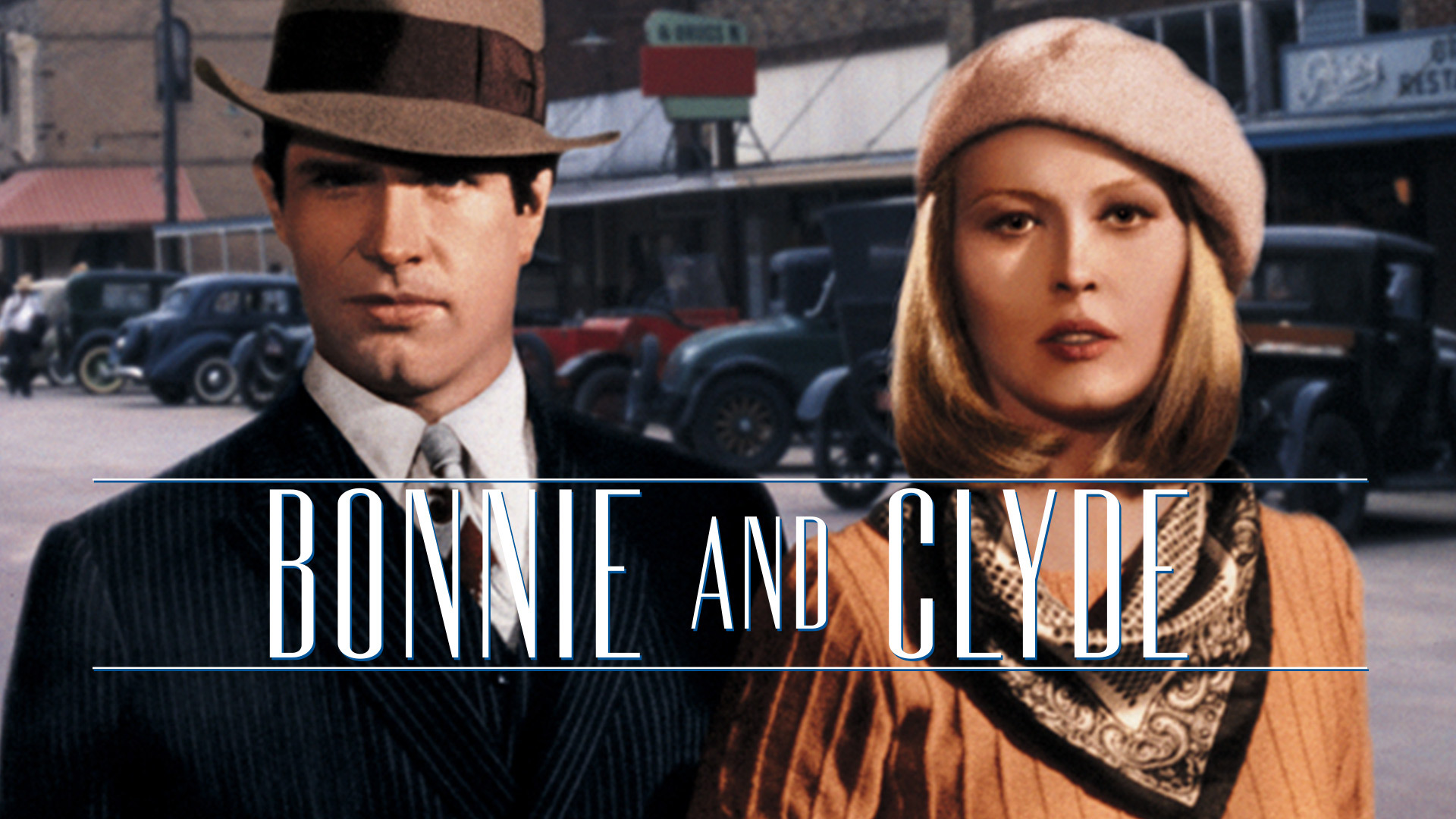

But the genie had already escaped the bottle. Despite some scathing reviews charging the film with gross historical and moral irresponsibility – The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther dismissed it as “a cheap piece of bald-faced slapstick” – the movie simply wouldn’t do what Bonnie (Faye Dunaway) and Clyde (Beatty) did at the shattering, bullet-strewn crescendo of the story, which was lie down and die. In keeping with the period’s climate of generational and cultural revolt, the movie became a lightning rod for dissent, a bold and shattering symbol of a country at war with itself over the very purpose of movies in American life. To defend the film was to take a stand against conservatism, orthodoxy and pop cultural business-as-usual. But it was also to stake one’s claim in the countercultural upheavals of which Bonnie and Clyde was simply one more especially vivid sign of how the times were so dramatically a-changin’.

Not quite incidentally, it bears noting that Beatty, as the film’s producer and shepherd through the staid but collapsing studio system, had at one point hoped to cast Bob Dylan as Clyde Barrow. In diminutive stature and physical appearance, the game-changing folk singer not only resembled the real Barrow far more than the pretty-boy Beatty, but he represented the connection to the present that Beatty knew the movie must and needed to have. It isn’t known if Dylan was actually offered the role – one can only imagine Jack Warner’s reaction to that suggestion – but when Beatty signed on as star as well as producer, it didn’t need Dylan to make the point. In style, tone, structure and sheer kinetic excitement, the movie was as bracingly urgent, untamed and contemporary as anti-Vietnam protests, race riots and that year’s other seismic, genre-hopping entry in the brave new, generationally-cleaving cultural landscape, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

One story has it that Beatty, never shy in the adversarial company of powerful men, actually crawled on his hands and knees in Warner’s office to beg for the movie’s green light. Another has the ambivalently conciliatory Warner, utterly convinced the movie would sink into oblivion, offering Beatty an unprecedented 40 percent take of the movie’s profits instead of a customary minimal. In its first years in release, Bonnie and Clyde reaped some $500 million dollars at the box office. If money talks, it must have been howling in Jack Warner’s ear.

Like so many historical artifacts which seemed to change everything but whose influence is now taken for granted, Bonnie and Clyde may seem strangely much-ado to contemporary viewers. Director Arthur Penn’s strategy of hard-slash cross-cutting – influenced considerably by the French New Wave, ergo Francois Truffaut’s brief attachment to the production – which once seemed so radical and disorienting, is now more likely to seem primitive than ground-breaking. And the movie’s formerly startling approach to sex and violence is hardly likely to ruffle sensibilities honed on a virtual digital universe of previously transgressive actions and images. The same could be said for the movie’s once supremely controversial blend of comedy, bloodshed, romance and nihilism, a tonal alchemy now so common it’s almost as conventional today as My Fair Lady (Jack Warner’s idea of a perfect Warner Brothers movie) was in the years leading up to B&C. If one can muster the proper degree of contextual sensitivity when approaching the movie, it’s easier to understand why some people watched it and saw civilization crumbling on a dirty Texas backroad.

There’s another part of this story that bears remembering, and that’s how Beatty’s movie both ushered in the era of radical mainstream innovation that came to be called “The New Hollywood” and helped instigate a similar flowering in the realm of movie criticism. Let’s consider the case of Pauline Kael. An erstwhile San Francisco film programmer who wrote effervescently biting reviews in McCall’s and The New Republic, Kael made her bones by mercilessly attacking precisely the kind of mainstream box-office smashes Jack Warner held as gold standards. The Sound of Music, for instance, was “a sugar-coated lie that people seemed to want to eat,” and she was similarly moved to withering disdain by Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago and even A Hard Day’s Night. This didn’t sit well in the white-bread women’s magazine McCall’s, but neither did it in the more ostensibly progressive New Republic, where Kael landed after McCall’s dumped her for being too contrary.

In fact, it was for McCall’s that Kael wrote a fulsomely appreciative, nine-thousand-word review of Bonnie and Clyde in the late summer of 1967, and it was from McCall’s that she fled when the magazine refused to run the piece. Meanwhile, over at The New Yorker, Kael found a far more appreciative sensibility in editor-in-chief Wallace Shawn, who not only agreed to run the piece at its original length but offered Kael the gig (which she would hold until 1991) as the publication’s chief movie critic. She couldn’t have asked for a better platform or moment, and the piece was, in its way, as influential and game changing as the movie itself was – not to mention similarly besieged and blocked. In Beatty’s movie, Kael saw nothing less than a hill on which to pound a flag, a declaration of a new era born and an old consigned to wheezing redundancy.

“How do you make a good movie in this country without being jumped on?,” her piece asked as its opening shot over the bow: “Bonnie and Clyde is the most excitingly American movie since The Manchurian Candidate. The audience is alive to it. Our experience as we watch it has some connection with the way we reacted to movies in childhood: with how we came to love them and to feel they were ours – not an art that we learned over the years to appreciate but simply and immediately ours.”

This is infectious, irresistible stuff. She speaks as one with us (which is a preposterous presumption if you really think about it), and understands that loving movies is at bottom not an intellectual process but a felt one, and therefore even all the hating generated by B&C affirms the movie’s vitality, energy and passion. It’s what makes it, in her words “alive.” We can either hate it or love it because it gets under our skin, and that, for Kael is what makes movie-watching such a sensually immersive experience – something to which we must ultimately surrender. So, let us conclude with her beginning, not only of the piece she wrote, but the era she saw as now irretrievably upon the American movie-goer circa 1967. Something had been sprung which would not and could not again be contained.

In her slyly consensus-building tone, Kael continued: “When an American movie reaches people, when it makes them react, some of them think there must be something the matter with it – perhaps a law should be passed against it. Bonnie and Clyde brings into the almost frighteningly public world of movies things that people have been feeling and saying and writing about. And once something is said or done on the screens of the world, once it has entered mass art, it can never again belong to a minority, never again be the private possession of an educated, or ‘knowing,’ group. But even for that group there is an excitement in hearing its own private thoughts expressed out loud and in seeing something of its own sensibility become part of our common culture.”

I am not sure how precisely true this is, but I am certain of its intense appeal as an ideal. The world was a-changin’ all right, and it was, as Kael would have it, unfolding according to plan. Not Jack Warner’s maybe, but that of an entire generation ready for change and hungry for it.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram