Citizen Kael: The Legacy of Film Critic Pauline Kael

April 15, 2020 By Go BackI don’t remember the first Pauline Kael book I read, but I do remember this: I hesitated for years because I couldn’t imagine a so-called ‘movie’ book without pictures. And Kael’s books never had pictures. At least not of the kind I expected of a movie book. What I hadn’t considered was that her books (nearly all collections of essays first published in The New Yorker) had pictures galore, only of rather different, literary kind: “This movie is a toupee made up to look like honest baldness.”

Quotes like this are abundant in Rob Garver’s What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael. They punch out from the screen in a flurry of Kael’s greatest hits zingers, but if pictures are worth a thousand words, Kael’s brand of atomic-strength criticism frequently seemed better than a thousand moving pictures.

Among the many pictures Kael’s writing installed in my head, there was this: “Kevin Costner has feathers in his hair and feathers in his head. The Indians should have called him ‘Plays with Camera.’” Clearly, here was a writer who was not only unafraid to tilt away from popular opinion (you’ll recall that the critical consensus on Costner’s Dances With Wolves was almost entirely positive – fawning even), she did so with gusto, relish and a mind like a freshly unsheathed razor. Most importantly, at least as far as an impressionable young wannabe movie critic was concerned, Pauline Kael could write.

I’ve often been asked if I was influenced by Kael, and the answer has evolved over the years, from “No way. Not ever. Not a chance.” to “Who, of my generation especially, could possibly have not been influenced by her?” It was like denying Citizen Kane (which Kael once notoriously insisted was not Orson Welles’ vision, but screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz’s) changed Hollywood picture-making forever.

Yes, it was the writing that mattered. Simply put, nobody wrote about the movies like this diminutive Jewish single mother with an acid-dipped pen. (As if her critical bona fides needed further proof, Kael claimed to write everything in longhand. Somewhat less convincingly, she also claimed never, as in ever, to have watched a movie more than once. Clearly, this was b.s. Check out any of her more extensive pieces – like those on Bonnie and Clyde, Last Tango in Paris, Nashville or Kane itself – and ask yourself: is it possible to glean such insight, such withering and penetrating insight, after seeing something only once?

Kael might have been a genius, an artist and the so-called single-handed instigator of the ‘American New Wave’, but she wasn’t a camera. The pictures she conjured in words were simply too vivid and indelible to have been painted with a single dip of the quill. But I understood why she clung to the claim, no matter how definitively her own writing insisted otherwise. Like her subject – the movies, movie stars and our gobsmacked love of them – Kael was building her own mythology.

What She Said, Rob Garver’s new documentary about Kael, fascinates precisely because of this: hardly known as a real human being – let alone a woman, a mother, or a Jew – Kael’s formidable way with a word (whom her contemporary Molly Haskell says “had more testosterone than any male critic”) effectively built a firewall about the person behind it. Together with Brian Kellos’s biography “A Life in the Dark,” Kael’s barricades have been breached, but the woman behind the wall remains a surprisingly murky figure.

As well she should. Indeed, it was some of the mystery behind the byline, the entirely reasonable wondering just who the hell could write about movies like this, that held one captive to her prose. That and the irrefutable passion for film that drove the prose. Nobody loved movies like Kael – whose bibliography reads like a carnal confessional: I Lost it at the Movies, Deeper Into Movies, Reeling, Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang, Taking it All In, etc. – and nobody hated like her either. Taking the hint suggested by all those dirty double-entendred titles, Kael took movies personally. When they were good, they deserved nothing less than total infatuation, but when they were bad, well, you’d think she’d been dumped and betrayed by a lover.

I came to Kael rather sideways, having crossed a lane from my foremost teenage passion: music and music criticism. True, I was already hopelessly smitten by all things movie, but I hadn’t yet plunged into film criticism with the same suggestible zeal I had music writing. Which left me once again driving the wrong way: the fact was, many of the music critics I considered the very best – Griel Marcus, Lester Bangs, Robert Christgau – bore traces of Kael’s muscular influence in the way they wrote about what they were listening to.

The funny thing was, Kael wasn’t the even the only critic (or even the only female critic who was writing on the edge in those days: Manny Farber was equally eccentric and uncompromising; John Simon lifted Kael’s purple acerbity without her insight; and the most exciting cinematic movement of the day was the French New Wave, itself the result of a bunch of critics putting their money where their mouth is. So, what made Kael, you know Kael?

If you watch What She Said, you’ll get an idea of how this intensely private middle-aged Jewish lady from California became not only the most dangerous make-or-break movie critic or hers or any era (next to Kael, the late Roger Ebert was Pollyanna), but not as comprehensive an idea if you read Brian Kellow’s A Life in the Dark. For all Kael’s mastery of the language, swooning love of movies and legion of imitators, it wasn’t just Kael’s poison penmanship that created all the fuss. It was the fact she rose so spectacularly at a precise moment. And what a moment it was, and how utterly unrecognizable it may seem today.

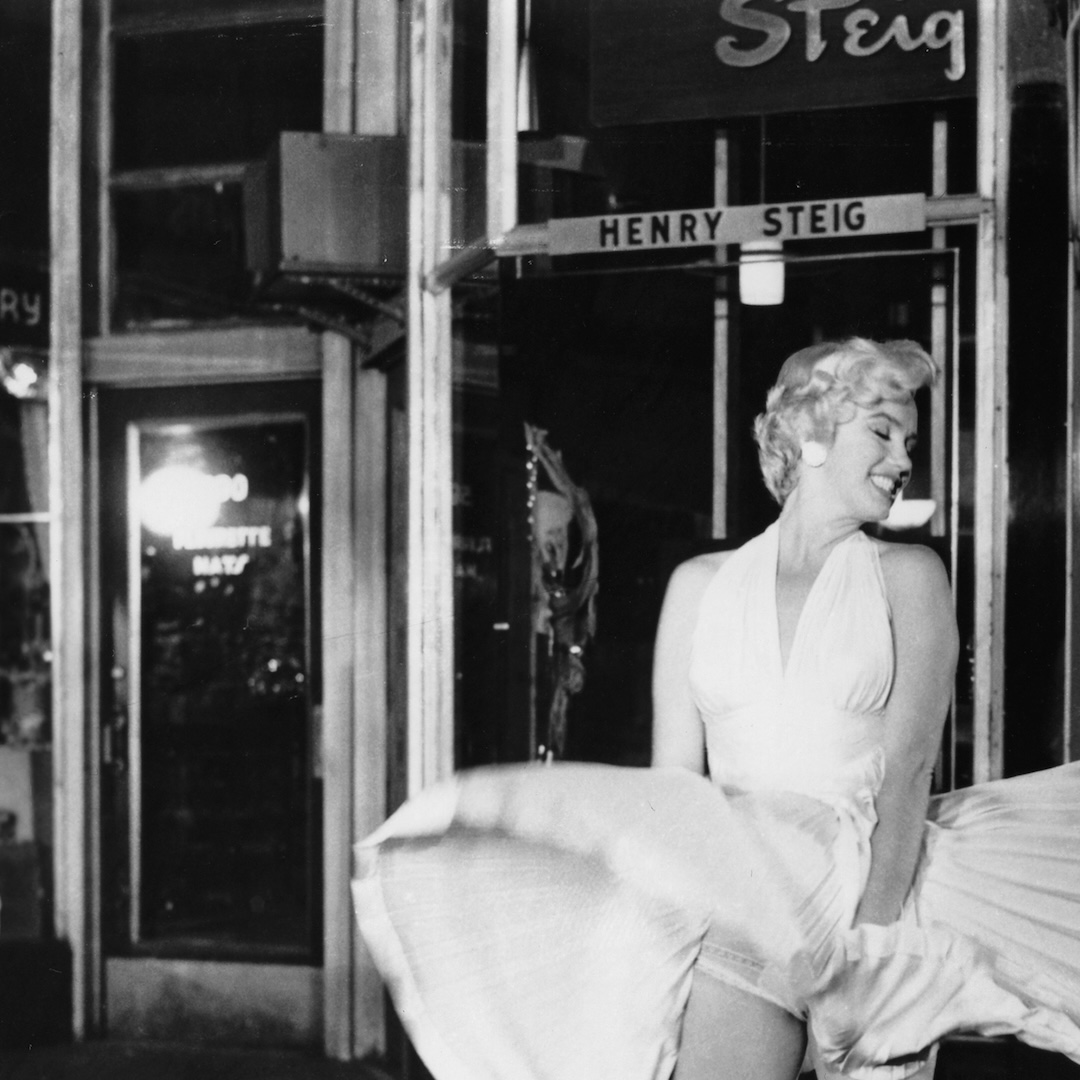

Recall that Kael’s coming-out as a critic to be reckoned with was her legendary, near epic October 1967 review of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, a movie steeped in New Waveish technique, attitude and cheeky nihilism. It has been called the most influential piece of movie writing ever, and, even if that’s stretching it, it ain’t far off.

Retrospectively, the impact of Kael’s Bonnie and Clyde essay is may seem unimaginable today, and it is. As often as I’ve heard people bemoan the absence of voices like Kael in today’s free-for-all, everybody’s-a-critic, fanboy digital universe, the truth is she couldn’t make anywhere near the impression she could through the late 1960s through 70s, an era of unprecedented maverickism and experimentation in American movies (and which some actually credit Kael’s B&C piece with igniting). This in turn was made possible by a movie industry so fiscally on-the-ropes it was desperate enough to try just about anything to stop the bleeding. Consider also that it was the heyday of long-form, risk-taking magazine journalism and criticism – a dead art if ever there was one. (It was this factor which also created a more or less simultaneous golden age in music writing – which is where I came in.) But mostly it was all these factors wrapped up in the utterly opaque idea of zeitgeist, which is a fancy German word for the spirit of the times.

Kael would never have watched movies with the same highly attuned radar for subversion and artistry at any other point in American culture and history, let alone dead centre in the middlebrow mainstream press. Questioning, subversion, skepticism, cynicism and irony: these were among the key defining elements in what became known (inevitably) as “New Hollywood,” and they could only flourish in that very brief moment when just about everybody was ripe for revolution.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram