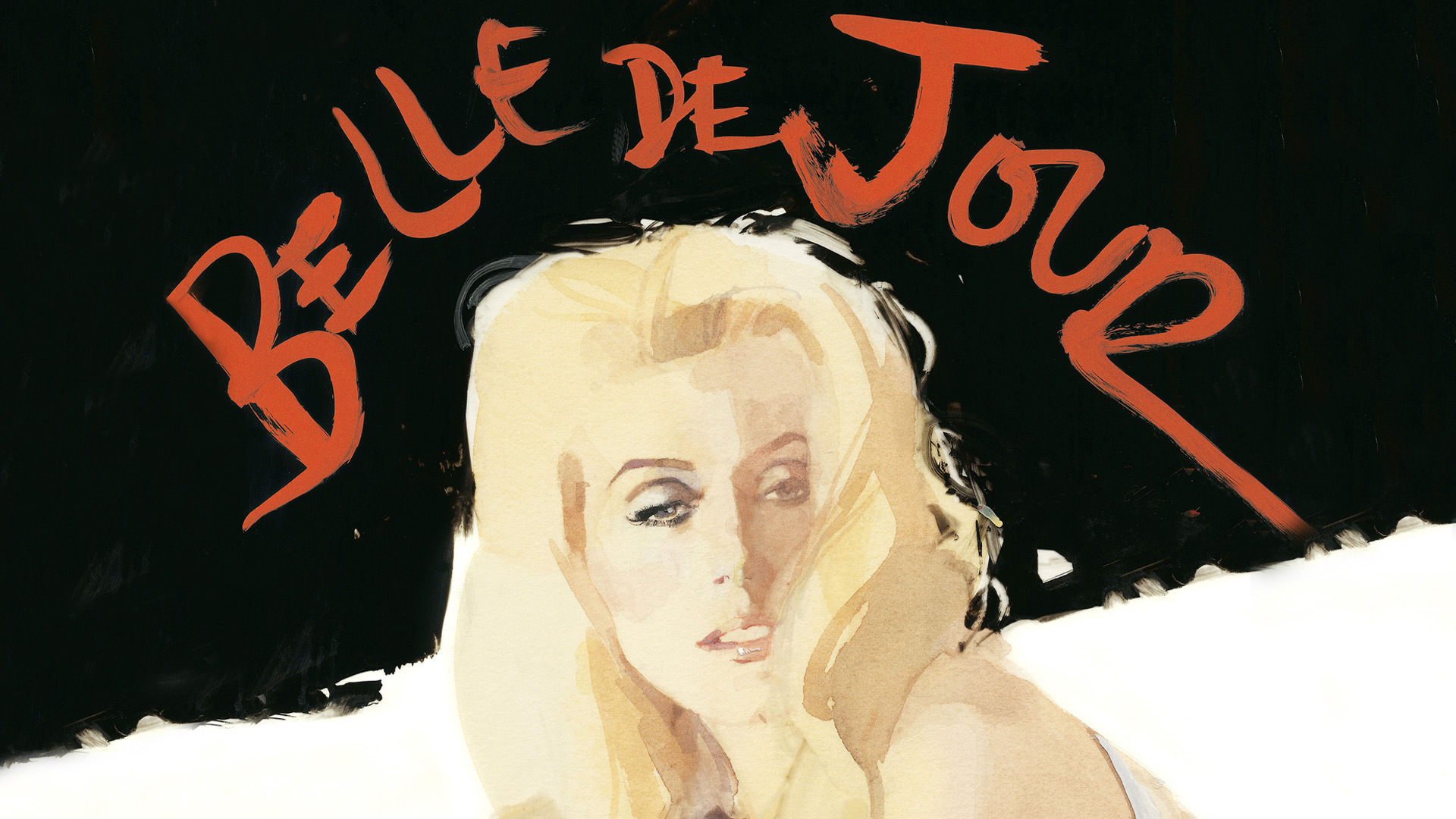

Belle De Jour: Buñuel’s Surrealist Erotic Masterpiece

April 5, 2017 By Go BackProvocative, trailblazing, and divisive, at various times in his career Luis Buñuel (1900-1983) was referred to as a revolutionary, an iconoclast, and, after one particularly notorious film release – 1930’s L’Age d’Or – the “Antichrist.” Today, more than thirty years after his death, he is universally acknowledged as one to the most important filmmakers of the twentieth century. The first certified surrealist filmmaker, Buñuel made waves in the silent era, when he and fellow Spaniard and college buddy Salvador Dalí directed the short Un Chien Andalou in 1929. Unconventional and rejecting narrative, its opening shot of a woman’s eyeball sliced with a straight razor by Buñuel himself (a trick that employed a dead calf’s eye) still stands as one of the most confrontational sequences in cinematic history. He was Hitchcock’s favourite filmmaker, which is perhaps unsurprising given Buñuel’s provocative, yet humorous approach. Several of his films make stalwart appearances on the most reputable top film lists. And, in the mid-1990s, after decades of unavailability, Martin Scorsese personally rereleased one of his most admired films – 1967’s Belle De Jour.

His most commercially successful, and perhaps most influential film thanks to its lasting impact on filmmaking, Belle De Jour is sexually explicit, transgressive, and truly visionary – it is also, thanks to an iconic performance from Catherine Deneuve, wildly arousing. Buñuel once claimed: “Sex without religion is like cooking an egg without salt. Sin gives more chances to desire.” Coming from someone who was educated under the strictures of the Jesuit priesthood, there is authority to the statement – Buñuel was as well versed in Catholic theology as he was in cuisine and libations (he was famed for his dry martini recipe, and once stated that “the decline of the aperitif may well be one of the most depressing phenomena of our time”). It is difficult to pin down meaning and significance in Buñuel’s films. He was too tongue-in-cheek and too slippery to know for sure – this is certainly true of Belle De Jour, which features a substantial dose of mystery, intrigue and possibility for open interpretation. Fantasy – the key theme of the film – co-mingles with reality, leading the viewer to constantly question what is real and what is not, and imparting a surreal, hypnotic tone to the film.

Deneuve plays Séverine Serizy, the young bourgeois wife of a successful surgeon (Jean Sorel). Handsome, patient and committed, her husband is frustrated by Séverine’s phobia of intimacy. Frigid and repulsed by his touch despite loving him, Séverine daydreams masochistic fantasies of submission, incorporating her husband and various strangers into her BDSM daydreams. When she learns of a local Parisian brothel that caters to an upper-class clientele, Séverine looks to make her fantasies a reality. Working exclusively in the afternoons – which garners her pseudonym “Beauty of the Day” – so that she can return to her domestic safety by the time her husband wants dinner, Séverine proves to be an easy study. Her initial trepidation melts away and erotic pleasure sweeps over her, ultimately improving her relationship with her husband, until a particular incident threatens to alert him to her side gig.

Even Buñuel could not have predicted the lasting impact Belle De Jour would have on the career and star persona of Deneuve. Primarily known for her angelic, virtuous roles in the films of Jacques Demy, including her breakout role in The Umbrellas Of Cherbourg, Deneuve would forever be associated with the image of Séverine in various compromising positions. Watching mud flung in Séverine’s aquiline, aristocratic face and her to-die-for Yves Saint Laurent-designed wardrobe torn and defiled in her dirtiest fantasies leaves the viewer wanting to see more – an implied voyeuristic tactic on Buñuel’s part. For Séverine, marriage is a trap; while it offers substantial comforts and care (her impersonal treatment of her servants is particularly interesting), the embrace of domesticity and romantic love is suffocating. For her, sex and love are divorced. By working at the brothel and discovering the full depth of her arousal she is empowered. Buñuel allows Séverine a secret life outside of the home without ever subjecting her “perversions” to ridicule or embarrassment. Her experience of her male clientele’s proclivities (which range from erotic ridicule, to necrophilia, to violence) allows her to discover her own sexuality outside the antiseptic set of twin marital beds

Buñuel intimately knew what he was subverting. He also knew how to be explicitly sexual without ever showing sex. It’s all cinematic foreplay – he cuts away from nudity and sexual acts – and instead, in typical Buñuelian form, creates a mysterious puzzle. When a client offers Séverine the contents of a lacquered box (after the other prostitutes have outright refused its offerings with disgust), Séverine is exceptionally turned on. Yet, the viewer is never allowed to know the nature of this gift. Buñuel claimed that “mystery is the essential element of every work of art,” and this clearly extended to the realm of sexuality. The surreal mystery in Belle De Jour, as well as the enigma surrounding its heroine, are what continues to captivate (and arouse) viewers 50 years after its initial release.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram