Why My Girl (1991) is Much More Than the Boy and the Bees

June 16, 2020 By Go BackWhen I tell someone that I love My Girl (1991), more times than not I am greeted with a look of utter confusion. “That movie with with the boy and the bees?” they ask, rolling their eyes. That’s when I ask them when they last watched My Girl. Usually, they can’t remember. Perhaps, they’ve never seen it at all.

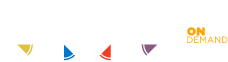

Over the past few decades, My Girl has definitely come to be known as a shameless tearjerker, namely due to the aforementioned moment involving Macaulay Culkin’s character and a fallen beehive. And while it is definitely a film that will wring the waterworks out of even the most heartless movie fans, My Girl is about much more than Culkin or what happens to his character.

Yes, Culkin certainly was a bigger star than My Girl‘s actual star, Anna Chlumsky, upon the film’s release, with the young actor hot off the mega hit Home Alone (1990). It’s why his face was featured alongside Chlumsky’s on the film’s poster and why his scenes continue to be referenced when talking about the film. But Culkin’s highly allergic Thomas J. is a just one of many side characters that populate the world of My Girl‘s lead character: the precocious and death-obsessed Vada Sultenfuss.

My Girl takes place during the summer of 1972 and it opens on 11-year-old Vada looking right at the camera as she lists the “afflictions” that she’s had to cope with thus far in her life (you know, jaundice, hemorrhoids, a chicken bone lodged in her throat). We go to a wide shot and see that Vada’s sitting next to her father, Harry (Canada’s own Dan Aykroyd) at a kitchen island as he makes sandwiches. Then, a straight-faced Vada turns to Harry and tells him that “[her] left breast is developing at a significantly faster rate than [her] right” and, as a result, she clearly has cancer and is dying. Without a beat, Harry ignores Vada’s claim and asks her to get some mayo out of the fridge.

As the movie goes on, we learn that all this medical melodrama is nothing more than big talk from Vada, a recurring symptom of having grown up in a funeral home (later she’ll claim to have prostate cancer after seeing it as a cause of death). We’ll also meet Vada’s other housemate, her grandmother Gramoo (Ann Nelson), who has Alzheimer’s disease and often communicates through random songs. Finally, we’ll find out that Mrs. Sultenfuss died while giving birth to Vada and the poor girl carries the guilt of “killing her mother” with her everywhere she goes like an overloaded backpack.

At just over a decade of life, Vada has spent a lot of time surrounded by discussions about death and dying, and it has informed not only her morbid sense of humour, but her general view of herself. But it is not until this particular summer that she gets to experience it first-hand, first with the arrival of the funeral home’s new makeup artist Shelly (Jamie Lee Curtis), and then with the passing of Thomas J.

You see, My Girl isn’t just about death in the literal sense. It is also about the death of innocence, or the painful transition from late childhood and into early adulthood. It is about love and loss, and dealing with both at the same time.

Before Vada gets the devastating news of Thomas J.’s death, she has to cope with Shelly’s growing romantic relationship with Harry, which she views as an emotional assault on the memory of the mother she never really knew. Vada also gets her period for the first time and finally learns about sex (from Shelly, of course, as her single dad hadn’t even thought to go there yet). On the romance front, she shares her first kiss with Thomas J. and learns that her crush (hunky teacher Mr. Bixler, played by Griffin Dunne) is not only not interested (and thank God), but taken.

To an adult viewer, these might not seem like particularly revelatory plot points. But to an 11-year-old girl, they would be huge, life-changing developments (this former 11-year-old girl should know). And what makes My Girl so special is that both screenwriter Laurice Elehwany (The Brady Bunch Movie, The Amazing Panda Adventure) and director Howard Zieff (Private Benjamin, The Main Event) treat these moments as such, giving Vada (and Chlumsky) the free space to be mad, sad and utterly confused about the changes being forced upon her both physically and emotionally. The film is narrated by Vada, as it is her story.

By the time we reach the climax of My Girl, with that iconic scene with Thomas J. and the bees, we have a firm understanding of who Vada is, not only as a young girl, but as a young person. This makes it hard not to be genuinely moved by the finale, with Vada coming to terms with her friend’s death and, in turn, her mother’s. We leave Vada on an uplifting note, with her finding comfort in new friends and creative writing, but we know that she will carry these two important figures with her as she continues to grow and evolve (see also: the equally underrated sequel, My Girl 2, where Vada goes to California to learn more about her late mom).

While the infamous funeral scene and intimate moments between Harry and Vada that follow remain truly thoughtful, the fact that these are the moments that My Girl is remembered for is a true tragedy. It is like saying that Stand By Me is a movie where boys find a dead body, or The Goonies is only about kids finding buried treasure. It robs the film of its nuance and changes the narrative around it.

If such male-dominated coming-of-age stories from the late 80s and early 90s can continue to be revisited by critics and audiences alike, My Girl should at least get a chance to be reconsidered as more than just a sob story co-starring Kevin McCallister. Even without the rose-tinted glasses that so often come with nostalgic favourites, it is a true hidden gem, a rare film that confronts the grief that comes with growing up specifically as a young woman. It is more than just the boy and the bees.

Find the next playtimes for My Girl (1991) on Hollywood Suite.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram