This Is Not An Exit: The Legacy of American Psycho

October 15, 2020 By Go BackBefore the American Psycho movie caused a scandal, the book, written by Bret Easton Ellis, did the same. Much of this controversy took place before publication; it was deemed so outrageous that Simon & Schuster dropped it, a month before it was scheduled to hit bookshelves. Granted, the story of a Wall Street yuppie turned serial killer named Patrick Bateman who tortures, murders, dismembers, and at several points, eats his victims is not exactly “family-friendly.” Ellis took all of this in stride; after all, he got to keep his $300,000 advance from Simon & Schuster and Vintage Books published the novel a few months later.

The movie adaptation was also beset by delays. David Cronenberg showed interest in directing, and Ellis, concerned that he wasn’t going to do the book justice, drafted his own screenplay. Director Mary Harron was asked to tackle it with her writing partner Guinevere Turner. Harron and Turner, much like Ellis, saw the book as a “critique of male misogyny, not an endorsement of it.” She and Turner completed a script, which Lion’s Gate, unbeknownst to her, sent to Leonardo DiCaprio, who had just exploded in popularity thanks to Titanic. Then Oliver Stone came on board. Harron was horrified.

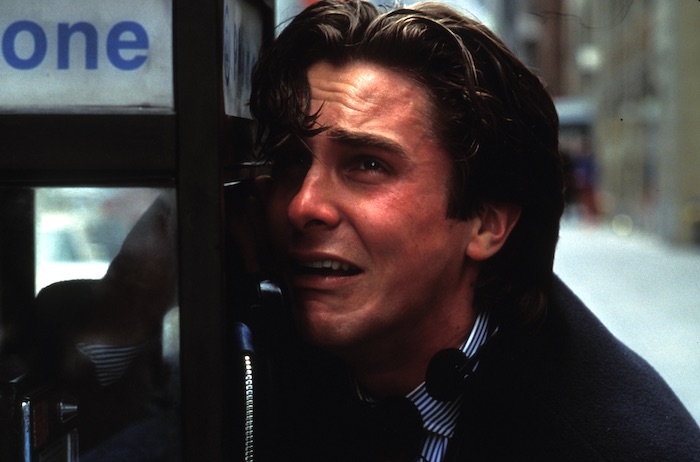

Yet she waited, convinced she was the right director for the film and that Christian Bale was the perfect choice for Patrick Bateman. Bale was unknown but not inexperienced; by 1999 he’d been acting for more than half his life, starring in Steven Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun when he was 13. Eventually, Harron’s tenacity prevailed; Stone left and Lion’s Gate came crawling back.

There was more controversy when the film started its Canadian shoot. A Toronto Sun article sensationally but erroneously linked the book to serial killer Paul Bernardo and nervous business owners backed out of location shoots. A group called C-CAVE — Canadians Concerned About Violence in Entertainment — sent faxes to local newspapers demanding citizens oppose the production on moral grounds.

Yet, nearly a decade after the book was originally optioned for the screen by producer Ed Pressman, American Psycho the movie was completed, debuting at Sundance on January 21, 2000. It cost $7 million to make but earned $34.3 million in box office receipts, not bad for a movie that was deemed “hideous and disgusting” before it was even filmed.

American Psycho’s massive return on investment is impressive, but the way Harron seizes on the original novel’s satire and exploits it for comic effect is nothing short of brilliant. Much of this is due to the film’s structure, which layers hilariously funny segments with short bursts of shocking violence.

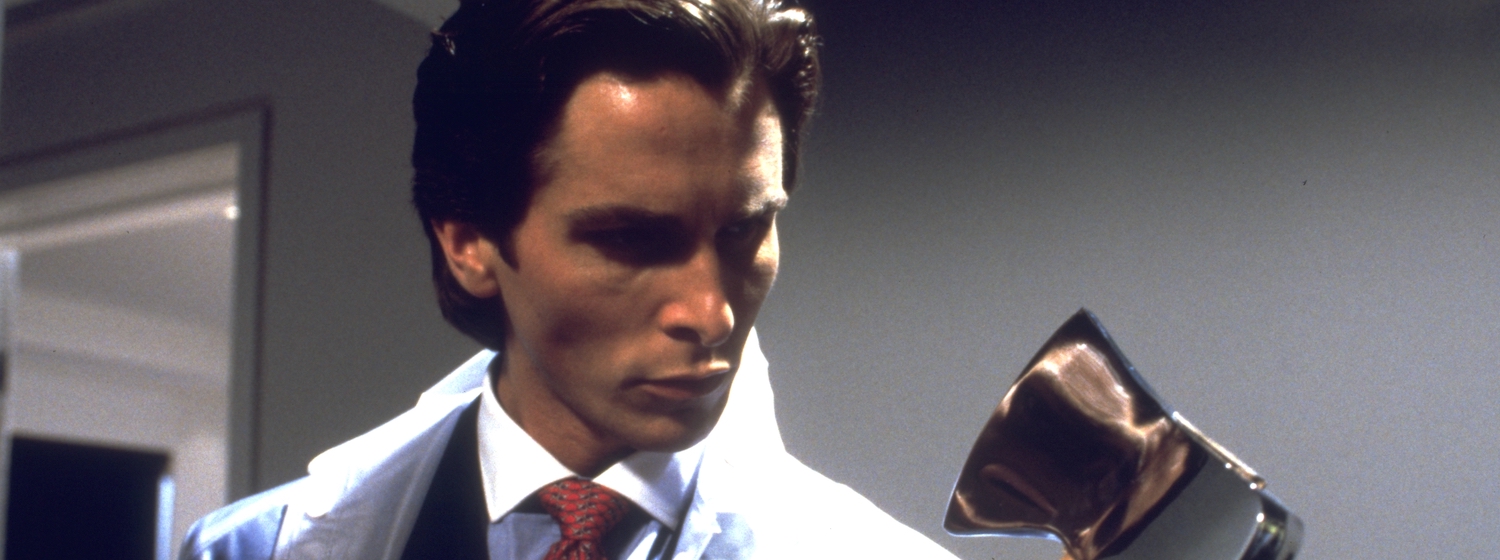

The most well-known example of this is when Patrick completes his first kill. He launches into an extended monologue on the genius of “Hip to Be Square” by Huey Lewis and The News, while moonwalking and dressed in a plastic raincoat. He then gleefully plants an ax in colleague Paul Allen’s head. Similarly, the infamous business card scene, during which Patrick succumbs to envious apoplexy over watermarks and font choices, is followed by a disturbing segment when he taunts and kills a homeless man and his dog. While many were turned off by the overwhelmingly graphic details in Ellis’ original prose, Harron utilizes tantalizing suspense to imply much of the violence or simply depicts it offscreen: the audience wants to look away but can’t.

Casting Bale (who showed up in character to a meeting with Ellis and disturbed him so much that he asked Bale to stop) was another inspired decision from Harron. Those used to seeing Bale in scenery-chewing mode (The Fighter) or after an extreme physical transformation (The Machinist, American Hustle, Vice) may have been surprised to learn that his earlier films relied on his innate ability to disappear into a role and portray a character through subtle micro-expressions (Little Women, Metroland, Velvet Goldmine). This skill is perfect for a character like Patrick Bateman, who can switch from a raging narcissist to a fool within seconds.

Although Ellis disagrees with Harron’s choice to portray Patrick’s bloodthirsty rampages as real and not the product of hallucinatory rage, the film can still be read both ways. So much of American Psycho is based on confusion, specifically mistaken identity, beginning with the very first scene where Patrick’s friend and co-worker can’t tell the difference between Paul Allen and Reed Robinson. (“Are you freebasing or what? That’s not Robinson.” “Well, who is it then?” “It’s Paul Allen.” “That’s not Paul Allen. Paul Allen’s on the other side of the room over there.”) Patrick himself is continuously mistaken by Paul Allen for another colleague named Marcus Halberstram, and later on, for someone named McCloy. Even Patrick’s own lawyer, Harold Carnes, doesn’t know who he is.

On a primal, more obvious level, Patrick killing Paul Allen is essentially Patrick committing suicide, but since Patrick’s personality is so diffuse it’s almost like he isn’t real. He even discusses this in one of his soliloquies: “There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman. Some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me… I simply am not there.” Furthermore, no one believes Patrick is a murderer because they all think Patrick is an idiot: Paul Allen calls him a “loser” and a “dork” and Carnes calls him a “boring, spineless lightweight.”

Regardless of whether or not the murders and executions Bateman engages in are real or fantasy, after 20 years, American Psycho feels more relevant than ever, especially in the age of 1980s nostalgia reboots and social media influencers with millions of Instagram followers but no discernable talent. Movie quotes like “my mask of sanity is beginning to slip” and “I have to return some videotapes” are the stuff of meme legend. Yet the influence of American Psycho is felt more deeply in other pop culture properties.

The most obvious is Bryan Fuller’s marvellous TV adaptation, Hannibal. In addition to a plastic “murder suit,” Hannibal Lecter, like Patrick Bateman, dons what his psychiatrist deems a “person suit.” He is not only a sociopath and a murderer but a cipher as well. Like Patrick, Hannibal kills people he deems unworthy or simply annoying. American Psycho’s opening titles could be utilized on one of Hannibal’s many cooking sequences: what looks like blood is actually raspberry sauce used to plate a meal at a posh restaurant.

More recently, the influence of American Psycho can be found in HBO’s Succession, particularly in the character of Kendall Roy. While family patriarch Logan might slay in the business world, Kendall is an actual murderer. Furthermore, his continual shifts between “good guy” (convincing the employees of Vaulter that he’s on their side) and “heartless monster” (firing everyone days later) feels like classic Patrick Bateman.

Perhaps American Psycho’s longest-lasting legacy, however, is that it allows audiences to live vicariously through it. In his review of the novel, New York Times critic Henry Bean remarks that Bateman’s “reality feels like a movie,” saying that his “touchstones” are “not murder but the fantasy and representation of murder.” We don’t need to kill people when Patrick Bateman can do it for us onscreen.

In the last shot of the film, during which Bateman states “this confession has meant nothing,” the sign on the door behind him reads THIS IS NOT AN EXIT. There may be no exit for Patrick Bateman, but thanks to the power of cinematic fiction, the world of American Psycho is one that the audience can leave behind or return to at any time.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram