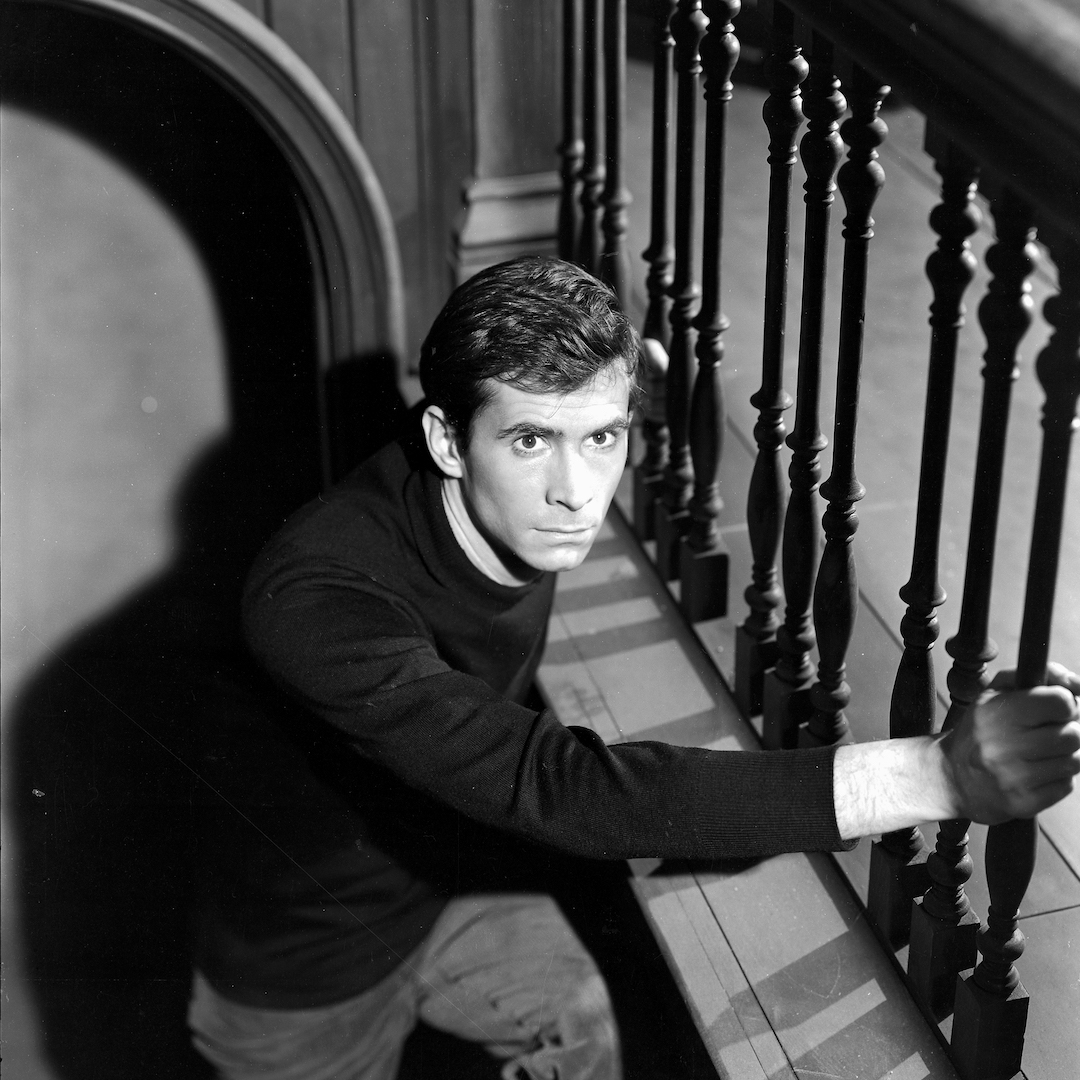

The Long Ride Home: Neil Sioux’s Legacy

September 23, 2022 By Go BackSteve Haining is the director of the documentary The Long Ride Home. The Long Ride Home will have its broadcast television premiere on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, September 30 at 9pm ET on HS00, and is available this September on Hollywood Suite On Demand.

Depending on how you grew up in North America, when you first watch the Long Ride Home, it can hit you differently. If you are anything like me – a caucasian man with settler grandparents who grew up in a big city – a lot of the stories, case studies and history shown, especially in the beginning of the film, may come as a shock, because though they depict documented history, they’re not often spoken of and seem to be intentionally kept out of educational curriculum. It hasn’t been until recent years that a voice has been echoing out of First Nations communities and non-indigenous people have been open to learning more and spreading the message to help bring justice to some of the tragedies in an otherwise forgotten dark history. Before this movement started in the past few years, Neil Sioux, an elder and my good friend who brought me on this film’s journey, was always looking for a way to get that message out. His message was that, “we know the past and we can learn from it, but we need to use the knowledge we have to build a future for our children so they don’t have to grow up lost, not knowing who they are, or suffering from intergenerational trauma.” He wanted to start at the source, and in a culturally relevant and traditional way, move forward to a better future.

In 2018, Neil told me in great detail about a dream he had. The dream was of a funeral, where in the distance Neil saw proud youth on horses. Having known Neil for a couple years, I could tell the dream had already inspired something powerful within his mind. Before I met Neil, I had spent at least a month or two every year teaching photography as a form of self-expression for youth dealing with trauma. I travelled all over the world doing this work; I was working in the Caribbean, I was supporting programs in Africa, really anywhere I felt I could make a real difference. At one point a few years into that, I was asked in a TV interview why I never did this work in my own country. I simply stated, “I’m going to the places that need it most, and that’s why I’ve been leaving Canada.” That interviewer responded with “You’ve never been north or to the reserves, have you?” I hadn’t. When I got home, I started Googling. That’s when I discovered all the stuff I had learned about the history of my own country was simply untrue. I learned that Indigenous communities have an extremely high suicide rate and the reserve with the highest suicide rate in Canada and the highest youth suicide rate in the entire world was located in my own province. At that moment my mind shifted to doing those art-based social work programs in my own country, specifically on reserves, and in remote communities and youth prisons that had high numbers of indigenous youth. This is how I met Neil Sioux.

Neil would always joke when introducing me to others that he had met me in prison. Neil used to be the cultural support and mental health worker in a maximum-security youth prison in Western Canada where I also worked – so while the statement was funny, it was technically true. When Neil left that project, he went back to treaty 4 and 6 territory, a place where there is a lot of trauma from residential schools, a lot of generational racism, and a place where there are Indigenous people that have their own conflict with other Indigenous cultures in the area. Neil was Dakota, and always stated that the Dakota people were never meant to be in Cree territory in Canada; they’re actually from the Dakota States in the USA. However, after the Dakota Uprising of 1862 was brutally put down by the US army, culminating in the largest mass execution in US history (of the Dakota 38 + 2) under the orders of Abraham Lincoln, many Dakota people fled and ended up in what is now Canada. When the reserve system was built, Canada generalized all Indigenous people in a region and planted them on reserves together. It would be similar to telling Italy and Germany they are the same because they are from Europe. Neil saw this problem there and was working in the community specifically with the schools and the youth in care. He had me and some other friends of mine assist on several projects to help get the youth creating and using art to deal with trauma and use it as a positive coping mechanism, and his process was incredible. He kept having us back over and over for years, and we were seeing success. We developed what was one of the best friendships of my life.

It was because of this relationship built on making positive change that Neil came to me with the idea that came from his dream. Based around the medicine wheel, which is broken into four, he was going to do four rides. These four rides were going to be six hundred kilometres long, over two weeks. The rides would go through indigenous reserves of different cultures, to show that despite their differences, they are together with their trauma and issues. He hoped to inspire them to work together to make a brighter future for their youth, and to learn from their elders while they’re with still us. He also hoped to bring awareness to their history and build a concrete positive path forward. The ride would start at the northernmost reserve supported by QBOW (An indigenous-based child foster care organization) and head south to the Canada/USA border where the Dakota ride from the south ends as well. And he wanted me to be there on the first ride to document it as current indigenous history and to share with other communities.

My response was initially no. If I remember correctly my wording was “I don’t want to be the tattooed white guy telling an Indigenous story,” because growing up, all I heard in school was the colonizer perspective of someone else’s history. Neil respected my decision and was fine with it, but every couple of months he would call me again to chat and it would come up in conversation. One day he told me he has known me for several years; he has seen me document stories a lot over that time, and that he trusted me as a friend. He went on to explain how it’s not about culture, it’s about being able to have someone he trusts tell the story openly and honestly and that’s why he needed me to be that person.

Of course, since the film is out and my name is somewhere in the credits, his words were strong enough to have me be excited to work on the film for him and tell his story. I could honestly not be happier that I finally said yes to his request because not only was that film and first ride so successful that it led to a bigger second one, but the film itself spread so quickly through the communities and across the world that now people like you who are learning about it have the ability to see and learn about it. The first film presents a lot of ideas that need to be taken with an open mind and the second one is quite direct with the ride’s intentions. The experiences and knowledge I learned on these rides and the relationships I built I will stay with me for the rest of my life, and I hope that you learn from them and have some compassion for the messages you may receive.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram