How the Wizard of Oz Has Endured for Generations

August 18, 2020 By Go BackHard-wired as it is to pop cultural consciousness, The Wizard of Oz is one of those rare movies the world is almost unimaginable not having. Imagine removing “follow the yellow brick road,” “I’m off the see the Wizard,” “Something tells me we’re not in Kansas anymore” or “Surrender Dorothy” from the collective stockpile of universal references. The hole it would leave would do a Kansas twister proud.

Now over eighty years old, The Wizard of Oz clearly has an allure that transcends just about everything. (Check out the movie’s IMDB listing. The “Did You Know” trivia section is endless.) How many other movies from 1939 still have such cultural currency? More people know Gone with the Wind than have seen it; Stagecoach remains landlocked in Western genre history; Lost Horizon (in some regards a grownup Wizard) is largely lost to the mists of Shangri-La. But Oz? It may be the only movie of its vintage that seems to seep perpetually into new generations.

Why? As enduring and popular as L. Frank Baum’s original book (and multiple subsequent Oz novels) were and remain, and despite several adaptations, sequels, fiction, theatrical adaptations and cartoon spin-offs, it’s the 1939 version that we carry everywhere in our subconscious. Just consider, for instance, the success of the novel and Broadway versions of Wicked, a perspective-switching piece of fantasy fiction that presumes sufficient familiarity with the characters and plot of Oz to understand the tale as told from the perspective of the Wicked Witch of the West. The novels, each a little weirder (and often darker) than the previous, are considered a landmark in fiction for introducing the first purely American fantasy novel for young readers, and for incorporating some of the deepest and most enduring national myths: the regenerating power of the frontier, the pluck of the all-American spirit, the fear of paternal abandonment, and of course the binary opposition of good and evil. Most of these are at play in both the books and ‘39 Oz, with the movie’s own original masterstroke: framing Dorothy’s journey to Oz as a dream, and exposing the Wizard as just another carnival-barking fraud. Which brings us to another reason Oz still rules: what could be more American than a movie about the intoxicating power of showbiz? Oz is both about dreaming and disappointment, and the figure of the flustered old man caught desperately pulling on levers once the curtain has been pulled to expose the “Wizard” for what he is. Like so much American fiction and pop culture, Oz both asks us to dream, and to be skeptical of the dreaming.

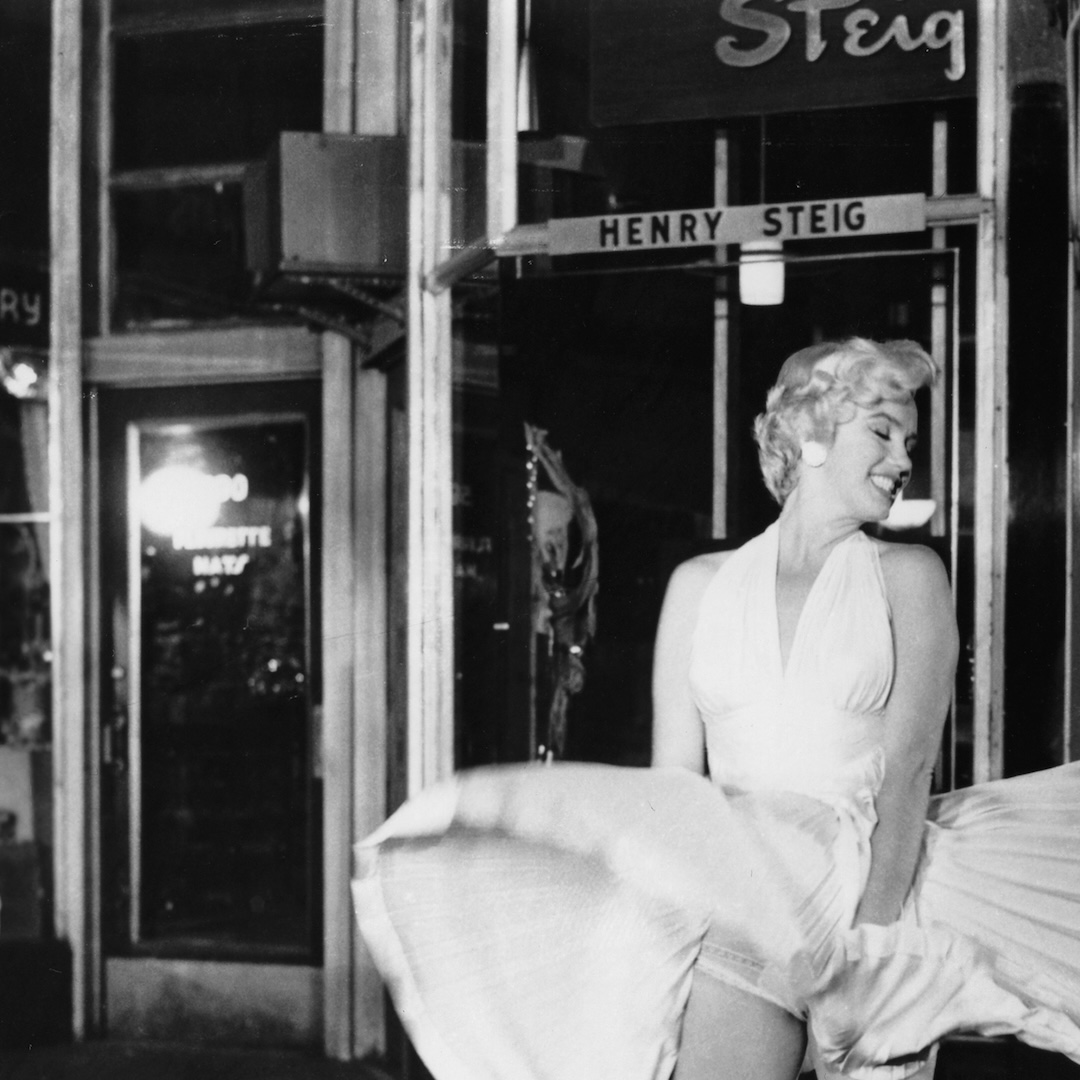

But what a dream the movie itself is, prompting such fabulists as Luis Buñuel, Salman Rushdie and David Lynch to consider it essential. I remember watching it more than not in pajamas, almost as fitting a setting as rapt in a movie theatre. Oz’s biggest and most impressionable audience would be those legions of kids like me who grew up in the black-and-white to full colour swing of the 50s and 60s. Maybe the most momentous decision of the movie’s entire legacy was made by CBS, who showed the movie at 6 pm instead of later in the evening to transfix as many kids as possible. The special schedule itself created a sense of event from these broadcasts, not to mention their airing between Christmas and Easter holidays. This made Oz something more than just a movie: it became a ritual, but not without a certain mass psychic cost. I don’t think any other movie in the history of cinema freaked more kids out. I know it did me, which is why it was heartening recently to hear somebody in their twenties tell me they still have nightmares about those flying monkeys. On a deeper level, Oz tapped a generation’s fear of abandonment, helplessness, loss, and monsters in the dark. Nothing did more seal Oz’s perennial classic status than those holiday network screenings, and this was true even before most people could even see Dorothy’s shift from sepia to technicolor reality. Even in black and white, this movie cast its spell.

Speaking of pulling back curtains, despite multiple volumes covering the movie’s troubled and fractured production – no less than five directors worked on Oz – the movie itself has proven to be largely resilient to fact. No matter how much is known about its production, it’s the myths that stick: the stories of sybaritic Munchkins, the Wizard’s (Frank Morgan) predilection for booze; Judy Garland’s inconvenient puberty; the so-called “Hanging Munchkin” (my favourite); the uncanny synchronicity of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and Oz.

Find the next air times for The Wizard of Oz on Hollywood Suite.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram