Ghost in the Machine: Robocop (1987)

July 19, 2021 By Go Back“We shape our tools,” the media philosopher Marshall McLuhan once observed, “and thereafter our tools shape us.”

By the time the 80s rolled around, many of McLuhan’s ideas had gone mainstream, though the man himself didn’t live to see it (He died in 1980). Among these was the idea that we make machines that are extensions of our bodies, at least until our bodies virtually become machines themselves.

In 80s pop culture, this manifested in a fascination with bodies hand-tooled as machines. On the one hand there were impossibly muscled physiques like Stallone and Schwarzenegger, while on the other there was the literal commingling of hardware and flesh: William Gibson’s prototypical ‘cyberpunk’ novel Neuromancer was published in 1984, the same year Schwarzenegger broke as a superstar playing a cyborg in The Terminator. The same year, David Lynch fused technology and flesh in Dune. Two years earlier, filmmaker David Cronenberg hitched the human body to technology in Videodrome, and two years later Sigourney Weaver strapped herself into a humongous robot suit in Aliens. In 1989, Jean-Claude Van Damme, another impossibly muscled movie star, appeared as the title character in Cyborg, and the first instalment of the Japanese Ghost in the Shell manga franchise was released. The Star Wars variation was a universe full of talking anthropomorphic “droids”. And by 1990, Schwarzenegger himself sealed the deal in Terminator 2 with the help of a new technology called computer generated effects (which in itself allowed the virtual human body to become anything it wanted).

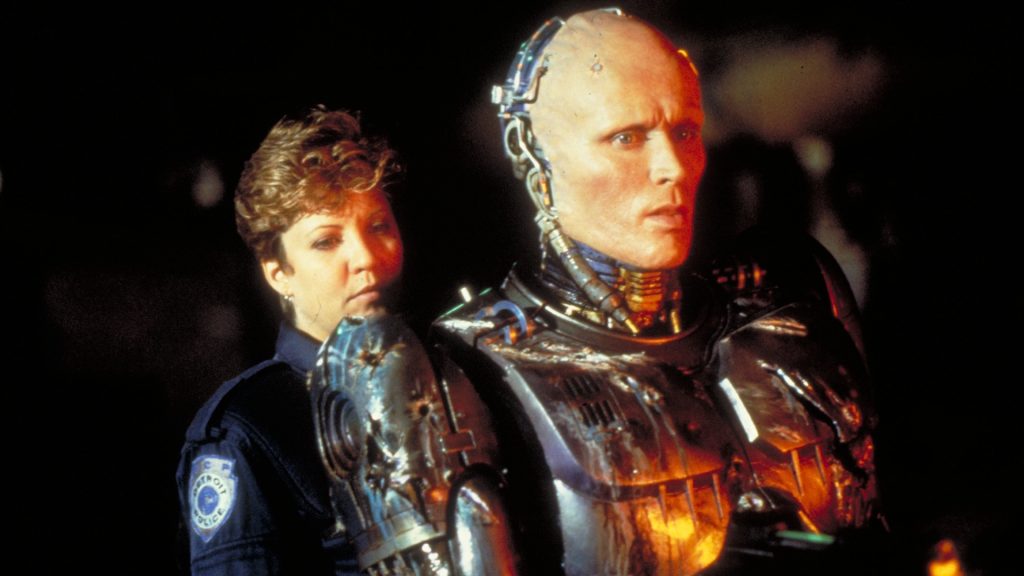

But certainly, the most memorable, vivid and influential of all these excursions into interfacing human/machine hybrids was Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop. Itself a hybrid product, Verhoeven’s dystopian vision drew from McLuhan, Frankenstein, comics, The Terminator, revenge movies and ancient mythology in its depiction of an urban police state gone off the rails. Set in the near-rubble of Detroit, Robocop pitted a part-man, part-machine super-cop (developed by the same corporation which runs the police force) against ultraviolent criminal gangs, traffic violators, rapists and ultimately the suits who created him from the remains of the rookie cop Murphy. Nearly seven feet tall and equipped with all the modern technology available at the time, Robocop (Peter Weller) nevertheless has one significant chink in his armour: memories of his previous life keep slipping in and interfering with his program.

At once a satire, a science fiction parable, a pop cultural mashup and ode to the tenacity of the human spirit, Robocop – like The Terminator – was initially trounced by critics as an exercise in heavy metal meat-headed mayhem. Which it was, up to a point. Now considered a near-classic and a highlight of its decade, the movie was itself something of a stealth weapon: so effective was Robocop’s surface appeal as a pulp fantasy that its real agenda, like Murphy’s soul, could easily go unnoticed. Had he lived however, I’m sure Marshall McLuhan would have got it immediately.

A trashier Stanley Kubrick, the Dutch-born Verhoeven came to America after establishing his reputation in Europe. Among his preeminent skills was balancing straight-faced storytelling with ironic commentary, a knack which reached its apotheosis with Robocop (and surfaced later in Basic Instinct, Total Recall and Starship Troopers). From its fake news opening to the ultimate showdown between corporate mendacity and human feeling, Verhoeven’s movie performed an especially graceful fusion of brittle cynicism and romantic humanism. Here was a movie which allowed you to have your popcorn and eat it too. And boy is it brutal. By the time that Murphy recovers and asserts his humanity, he has been burned, beaten, shot and dismembered prior to his near-Biblical resurrection.

Although laced with memorable set-pieces (Murphy’s initial ordeal, a corporate boardroom blood-fest, and a final showdown in a very 80s industrial setting), Robocop’s tone and style remain consistently free of winks and nudges. The result keeps the audience just slightly unbalanced throughout, a fitting state for a movie about a heart encased in titanium.

Inevitably sequelized and re-made, Robocop remains sui generis for precisely these reasons: not since A Clockwork Orange had violence, thoughtfulness, social commentary and humour been so effectively held in balance. (And that movie, another target of critical hostility, also flew in its own orbit.)

Still audacious, prescient and a hell of a lot of unwholesome fun, Verhoeven’s cautionary urban fable is both landlocked in its 80s setting and enduringly relevant. The hair might be a little high and shoulders wide, but beneath that surface lies a warning for the ages. Or at least ages that put a premium on technology and compact computers in our pockets. If anything, Robocop, like the words of Marshall McLuhan, is only more pertinent now than ever.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram