Dirty Harry’s Daddy: The Big Heat

February 24, 2022 By Go BackOne of the fiercest of classic films noirs, Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat takes one of the 50’s principle preoccupations (urban vs. suburban) and blends it with one of the original ‘rogue cop’ narratives.

Sgt. Dave Bannion (Glenn Ford) is a cop in a small city. When called to investigate the apparent suicide of one of his colleagues, Bannion finds himself in the middle of, and targeted by, the local mob headed by the serpentine Mike Lagana. Although pressured to drop the investigation, Bannion presses on, in the process losing his badge and eventually his wife (Jocelyn Brando). The latter incident pushes Bannion to go vigilante, stopping at nothing to bring Lagana and his goons to justice. Though people will die as the result of Bannion’s driving obsession, he clearly feels the collateral damage matters less than getting his revenge.

Bannion’s actions and attitude were unusual for a movie cop of the day, but eventually became a staple of crime films: the cop who, frustrated by bureaucratic protocol and frequently bent on revenge, strikes out on his own for justice. By the 70s, this figure was becoming a staple of the genre. If Dirty Harry had a daddy, it was The Big Heat.

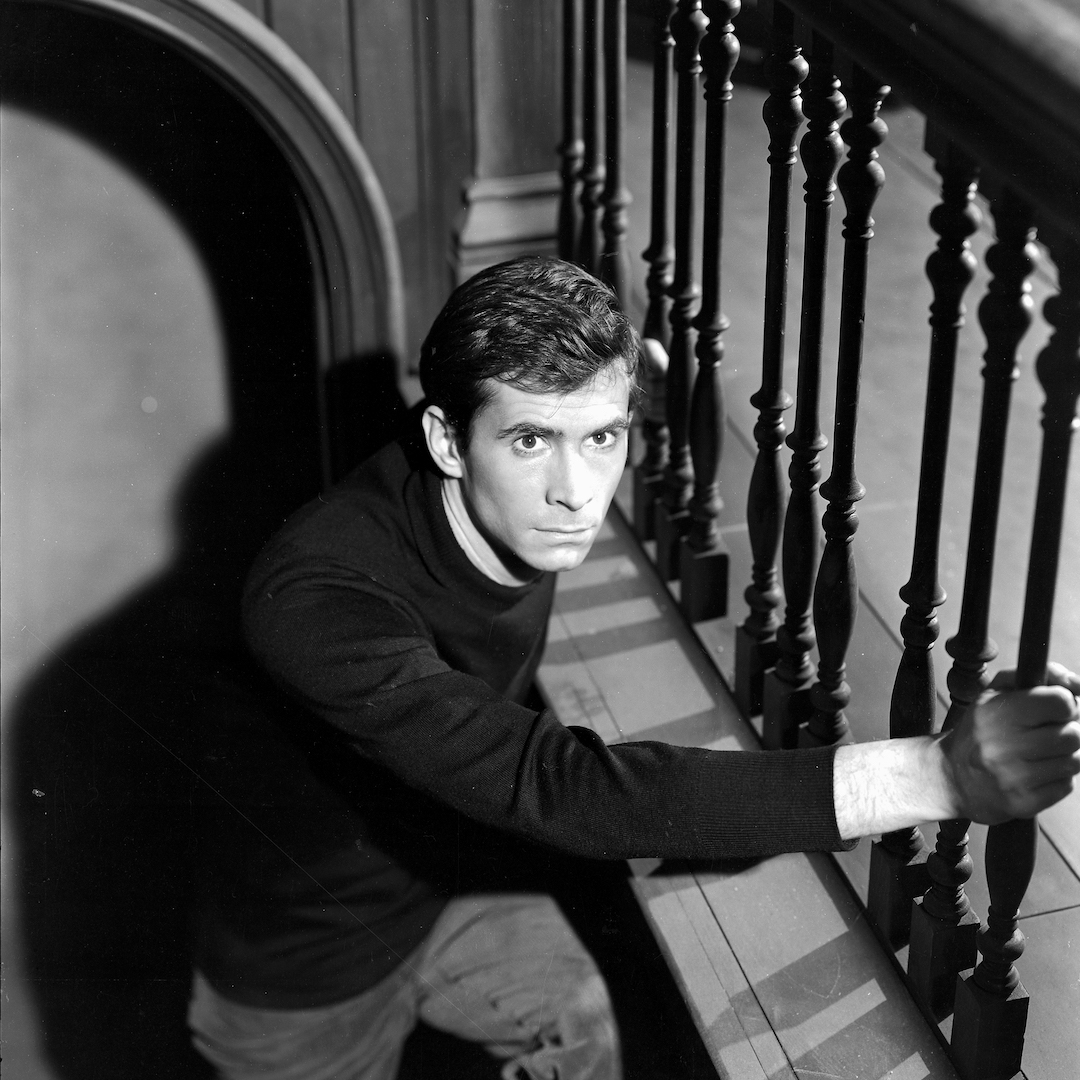

Born in Vienna in 1890, Fritz Lang is one of Hollywood history’s most intriguing figures. He started making films in his twenties, which led to his hiring by Germany’s largest and most prestigious studio, UFA. During the silent era, which was also the heyday of the style called expressionism, Lang forged a visual style while turning out some of the most popular and influential movies of the era.

Lang was a consummate visual stylist, and his early works are essential to an understanding of how Expressionism (which favours psychological over physical reality) fed the postwar cycle of crime films) heavily influenced film noir. When Lang started making movies in Hollywood he specialized in the dark, brooding, fateful dramas that came to be called noir. The city was a cauldron of corruption and murder, a perspective that defined Lang’s best known German films, Metropolis and M and carried over into his Hollywood productions.

One of the most famous stories in Lang’s biography sees the director being summoned to the office of Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels and offered a job as head of UFA. Fully aware that the discovery of his mother’s Jewish roots could lead his arrest and possibly death, Lang hopped on a train for Paris that evening. From there he headed west to Hollywood.

Joining hundreds of emigres from Europe who fled to Hollywood as storm clouds gathered, Lang was quickly employed directing mostly medium to low budget dramas, but even in reduced circumstances the director maintained his vision. His films were thick with expressionistic shadows and attitude. His protagonists tended to be ordinary people who stumble in those shadows, rarely ever to return. Both Lang’s style and temperament were perfect for the as-yet-unnamed genre of film noir. Significantly, it would be French critics who named this tendency in the American crime film, and from the beginning Lang was cited as a consummate example of the emerging auteur theory.

Often criticized for being pessimistic or cynical, the Austrian director was undoubtedly motivated by stories of greed, betrayal and suffering. But these attitudes were so seamlessly integrated into the style and content of Lang’s films they seemed organic. His favourite subject seemed to be people trapped by fate and circumstance. For instance, when Bannion decides to function as an extracurricular enforcer, it sets him on course for a mission that will not only leave several people dead, it turns the cop himself into a driven avenger, a man who, by the end, looks like he might never make it back to suburbia.

Suburbia in The Big Heat may be a refuge from the corruption and violence of the city, but it proves all too vulnerable to the mob. When Bannion’s wife is killed by a car bomb in their tidy driveway, it proves that crime knows no borders and suburbia itself is ripe for exploitation and ruin. This at a time when Americans were flocking to the suburbs by the millions, many thousands of whom were on the run from the cauldron of the city. Lang was emphasizing the impossibility of living safely anywhere. Evil spreads like suburban sprawl.

Follow us on Instagram

Follow us on Instagram